1947-02-24, #1: Doctors' Trial (early morning)

Official transcript of the American Military Tribunal in the matter of the United States of America, against Karl Brandt, et al, defendants, sitting at Nurnberg, Germany, on 24 February 1947, 0930, Judge Beals presiding.

THE MARSHAL: Persons in the courtroom will please find their sets. The Honorable, the Judges of Military Tribunal 1.

Military Tribunal I is now in session. God save the United States of America and this honorable Tribunal.

There will be order in the court.

THE PRESIDENT: Mr. Marshal, you ascertain that the defendants are all present in court.

THE MARSHAL: May it please your Honor, the defendant Oberheuser is absent due to illness.

THE PRESIDENT: The rest of the defendants are present?

THE MARSHAL: The rest of the defendants are present, sir.

THE PRESIDENT: Defendant Oberheuser, having filed with the Tribunal a certificate of Roy A. Martin, Medical Corps, U.S. Army, that she is unable to attend court this day on account of illness the defendant will be excused, it appearing to the Tribunal that her absence from the Tribunal today will not prejudice her right.

The Secretary-General will file the medical certificate of Doctor Martin. Counsel may proceed.

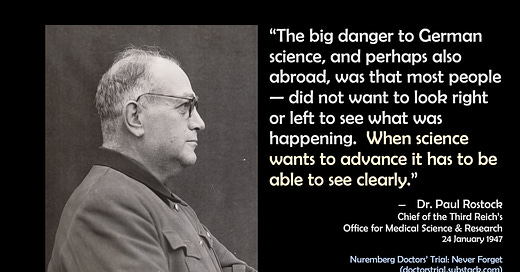

PAUL ROSTOCK — Resumed

DR. PRIBILLA (Counsel for the Defendant Rostock): Mr. President, I ask you to excuse me that I am turning to the Tribunal at this time. At the end of the last session the defendant was asked some questions by the Tribunal. Mr. McHaney was kind enough to draw my attention to the fact that the witness didn't quite understand one of the questions of Judge Sebring, perhaps because of some misunderstanding. My own observation confirmed his and we are concerned with the following. Judge Sebring asked Rostock Ex. No. 4, Page 7, where there is a publication of Rostock's about sulfanilamide. He asked where Rostock received the date for that publication.

To understood that Judge Sebring wanted to ask from where he received the material basis for that lecture. The defendant, however, always answered continually in such a manner which led one to believe that he meant that the question was about the reliability of his statement as contained in the document. If Judge Sebring is of the same opinion. I would suggest we clarify this point again before answering any more questions.

JUDGE SEBRING: As I understand it, the purpose of Rostock Document No. 5 was to show to the Tribunal the extend of the work done by Professor Rostock in the publication field, Roman I showing the books which had been written and published by him since the middle of 1937, Roman II showing the articles which had been published by him, I take it, in medical journals and other published works of that nature. Is that correct?

THE WITNESS: Yes, that is correct.

BY JUDGE SEBRING:

Q: The Tribunal was interested in knowing something about the general publication "Treatment of War Wounds with Sulfonamides, Report of Congress East of Consulting Physicians, 1942". Perhaps to further clarify the matter it might be appropriate to ask this question: What was the nature and content of that article that appeared as a journal publication?

A: As a matter of fact, I really misunderstood the question as was put to me on Friday, after what I have heard today. Friday I believed that I was asked on what basis I incorporated this article in that list, namely, Exhibit No. 5. Naturally, it is very easy for me to answer the question as to what my explanations were based on in the year 1942. That was based upon my own experience during two and a half years of war. That was based on studies of literature which was published, and, furthermore, the consulting surgeon with the Army Medical Inspectorate sent me the experience reports of other surgeons of the Army in that field. In order to an answer the other question at the same time, I should like to say that I didn't receive a report from Mr. Gebhardt.

That wasn't at my disposal at that time. When at the time I hold this lecture the experiments of Mr. Gebhardt, which are subjects of discussion here, had not even started. According to this list they began in July of 1942. I don't know whether I have answered your question with that.

Q: Professor Rostock, do you recollect at this time the date or the month and year in which this article was published and made available to the medical public in Germany?

A: The lecture was held in the middle of May, 1942. I can't give you the exact date. Maybe I could look it up. It appeared in print, that is, in these reports of the consulting physicians that were submitted here, and I assume that was published in the summer or fall of the same year. They were not published in the same manner as would be the case with a periodical, but they were published in an official printed matter which was not secret and were put at the disposal of the military physicians. That is how they appeared in print.

Q: So far as you know, were they put at the disposal of the medical officers of the Waffen-SS?

A: I don't know that. Perhaps Generaloberstabsarzt Handloser could answer that. I know they were sent to the physicians of the army. I don't know who else received them.

CROSS EXAMINATION RESUMED

BY MR. McHANEY:

Q: Herr Professor, do you remember what conclusions you drew in this lecture on sulfonamide in May, 1942?

A: I merely initiated the basic research work about which we spoke on Friday, and, according to the knowledge which we had at that time, I gave some basic outlines as to how treatment was to be carried out and I pointed out a few questions which had not been cleared up in that field. I could explain that in greater detail if I could look through the wording of the lecture once more.

Q: Did you draw any conclusions with respect to the necessity of having front line hospitals with surgical treatment of soldiers with wound infection as against the possibility of treating such wounded soldiers with sulfanilamide and evacuating them to the rear?

A: Sulfanilamide treatment in itself was customary in many places at the front.

There weren't any special hospitals for that purpose and they were hardly possible at the moment. Our entire difficulty was that, under conditions of war, every physician who took care of the initial wound, of the wound dressing, only kept the patients for a few days under his own observation since the medical stations and hospitals at the front had to be evacuated very speedily in order to keep them ready for new wounded who might come in, and this change just during the first decisive days made it practically almost impossible for one surgeon to care for such a patient from the wound dressing up until ten to fourteen days later and keep him under constant observation. And during these ten to mostly fourteen days the wound development decides itself.

Q: Now, Professor, the sulfanilamide experiments of Gebhardt have been rationalized to some extent by the statement that German military medicine was undecided as to the value of sulfanilamide treatment and, that if certain problems could be cleared up in that respect it could be determined whether it was possible to cut down on the treatment of wounds with surgery in the front line hospitals and merely treat the soldier with sulfonamide and evacuate him to the rear or whether, on the other hand, it was necessary to build up, to increase the number of front line hospitals because it was necessary to treat these wound infections with surgery. Do you understand that?

A: If I understood the interpreter correctly that certainly was the problem. Was I to treat the wound with surgical means — was I to use knife and scissors in order to remove the tissue in order to kill the basis for the bacteria or can I dispense with that treatment and can I think that it would be sufficient to put some powder into the wound? There was very much controversy about that question. There were followers and opponents for both of these extreme uses and only gradually the point of view prevailed that with reference to the ordinary wound infection the mere treatment of powder — that is sulfanilamide — in the wound itself would not be sufficient. But, in order to experience that and in order to arrive at that conclusion as we did we needed a number of years in view of the numerous wounds that occurred during the war.

That is because of the difficulties which I described before in the medical observation during the first days of the wound. In order to answer the question whether or not more hospitals had to be instituted — that, of course, would have been an expedient measure but I don't believe that it was possible from the personnel point of view for, in order to furnish a hospital, you need experienced physicians, and, as far as I could survey the situation of personnel, we hadn't enough. I remember a radio report which once came from America where an American high medical officer said: "We Americans shall win the war because we have four or five times as many physicians as the Axis powers." I don't dare to decide whether this view was correct or not.

Q: Did your paper, your lecture in May, 1942 shed any light on this problem as we have posed it here?

A: I'm sure I didn't express it with these words, but the question of whether to treat wounds surgically or only use powder was a question that was repeatedly contested.

Q: Now, you have testified concerning two conferences in 1944 to discuss special research and that Schreiber and Breuer of the Reich Research Council were present at these meetings. Who else was present and what agency did they represent?

A: This is how it was. The first meeting in the summer can be traced back to me. Present were gentlemen of the Reich Research Council, gentlemen of the Medical Inspectorates of the Wehrmacht’s branches and Reich Office for Economy and Building. It was just a very small circle. This took place in Bielitz, mainly because of air raid precautionary reasons. It probably would have been as well to choose a little room in Berlin for expediency but Berlin had become very troublesome at that time. The reason of this discussion — don't let's call it a conference — was that almost underhanded I heard that there were considerations pending in the Armament Ministry in order to stop research. These considerations were pending apparently for quite some time for the second meeting of which I also spoke only took place in the winter and was not initiated by me but by the Armament Ministry. And, there the circle was much larger for there were present about seventy or eighty gentlemen, mostly technicians. Any measures of the Armament Ministry were probably directed to technical research and the few gentlemen who did purely research work in the medical field only were so very few that they played no part whatsoever.

Q: Do you remember who represented the Wehrmacht at the first meeting?

A: I don't know. I believe Schreiber was there. I don't know who was there from the Luftwaffe or the Navy.

Q: Anyone represent the SS?

A: I can't remember exactly which one of the gentlemen was from the SS.

Q: Well, do you think there was someone there from the SS and you just don't remember his name?

A: I can't tell you that exactly.

Q: And, have I understood from your previous testimony that you discussed nothing at this meeting except what fields of research were urgent?

A: We discussed the question of what larger fields of research, considering the intensified conditions of the War, would be necessary in the future. We arrived at about twelve or fourteen such themes.

Q: Didn't you discuss particular research assignments?

A: Individual research assignments you mean? Assignments to Mr. so and so, is that what you mean?

Q: Yes.

A: It may have been possible but that could only have been used as an example. It wasn't done in a manner where a list or research assignments available came through in detail. Entire list perhaps was discussed. Naturally one of the participants, by way of example, mentioned any particular assignment —

Q: You say you did not go through a large list of research assignments and pick out certain individual ones and designate them as urgent?

A: We designated the entire field. Naturally the gentleman who had distributed these orders had to use their own discretion whether they wanted to drop one or the other. That wasn't my task to decide and I had no power to do that.

Q: You yourself did not designate specific research assignments as being urgent?

A: Naturally it is quite possible and thinkable that if somebody said that I give this assignment to so and so and would say, "please think about it" — quite natural I would give my opinion on the subject. But, without having my material at my disposal I could hardly answer that here under oath. I think that will be the case with many gentlemen here. I don't know whether if one of the defense counsel who would be asked here what happened during a trial three years ago, whether they remember all the details of that trial — maybe they could discuss it if they had their files. I would be able to do that if I had my files and could look it up, but merely from memory, considering the time that has lapsed it is something too much to ask.

Q: Well, do you remember what you did following the first meeting? What results occurred as a result of this meeting?

A: As a result of this meeting a list was made about these twelve research fields which were considered important. That was sent to Ministry Speer and to other agencies.

Q: Now, didn't all of this really require some knowledge of just what a particular scientist was doing? And how he was doing it?

A: No, not at all. It wasn't necessary to decide whether, in order to give an example of this trial, whether to know what Haagen carried out in way of typhus vaccine experiments. It was sufficient to know that typhus danger was very large for Germany and we had to say to ourselves that we had to protect Germany against this danger — that we had to continue to work — and in order to arrive at this realization it wasn't necessary to know any details which were carried out in some typhus hospital somewhere. The decision of importance could be arrived at without any of the detailed knowledge that were in the individual's sphere.

Q: Now, I take it that you were getting together your card index file of special research assignments before this meeting took place in the summer of 1944. Is that right?

A: Yes. A little before that.

Q: What use did you ever make of this card index file of research assignments?

A: It didn't really find a proper use. As I said the actual threatened interferences in research activity by the Armament Ministry only came about in the winter and whoever can remember what Germany looked like during the winter of 1944-1945 will agree with me that at that time directives from above had no value any longer. In most cases they didn't reach the agency they were directed to. I think that the number of mail that was burned was very large and extensive.

Q: Didn't you have any correspondence with these scientists who were working on special research assignments? Didn't you send general instructions to them of any sort, or things of that nature?

A: I certainly had correspondence with the scientists. As for general directives to individual gentlemen, that is something I didn't send. But, if somebody believed that he was to be limited in any way or some personnel was to be taken away from him or that his iron or material supply was to be cut down, then certainly he approached all agencies from who he hoped they could help him.

A: Did you ever circularize German scientists with any sort of instructions about what your task was, how you could help them in a given situation, just when it was they were supposed to get in touch with you?

A: I never sent a general directive of that nature. This would have had to be printed considering the amount of people involved and I cannot remember such a procedure. I certainly had individual correspondence with gentlemen that I knew.

Q: Did you know a man by the name of Schulemann, S-c-h-u-l-e-m-a-n-n?

A: Yes. I know Schulemann. He is the well known discoverer of the well known malaria drug "plasmochin". He was professor of pharmacology in Berlin.

Q: Do you know a man named Zeiss, Z-e-i-s-s?

A: Zeiss was professor for Hygiene in Berlin. I know him naturally. There is another Zeiss. There is a Zeiss in Magdeburg. I don't know which one is meant.

Q: Now you mentioned the correct one first — the Hygienist in Berlin. What about Dr. Pfaff, P-f-a-f-f?

A: Pfaff? Pfaff? At the moment I have no imagination when you mention that name. Maybe you could tell me more about him — was he a surgeon?

Q: Apparently he was an expert on tuberculosis.

A: I don't remember. If I think about the names that I know of German tuberculosis workers I don't think I heard anyone of that name in that connection.

Q: What about a man named Vezler?

A: Vezler? Yes. Vezler was a physiologist at Frankfurt-on-theMain, who worked on Taslau physiology.

Q: Did you know a man named Hildebrandt?

A: Here was a surgeon, Hildebrandt. He is dead. He was dead at that time. I don't know anything about him.

Q: I Have in mind a pharmacologist at Giessen.

A: No, I don't know him.

Q: What about Fischbeck?

A: I know the name from somewhere but at the moment I cannot say who he was.

Q: Schlossberger?

A: Yes. Schlossberger was a hygienist at Jena.

Q: Bachmann?

A: Bachmann? At the moment there is nothing I can remember under that name.

Q: Gremels?

A: Gremels? I don't know him.

Q: Butenandt?

A: Butenandt was a very well known physiological chemist and he is the man who discovered how the female sexual hormones were put together and did research work on that subject. He was at first in Berlin and then Tuebingen.

Q: Now, professor, isn't it a fact that German medical research is composed of a fairly close-knit body of scientists? Isn't it a reasonably tight organization in a country of this size?

A: No, certainly not. For instance, I know all the well known surgeons of Germany because of the yearly congresses which in normal times took place; but I never knew the expert representatives of other fields. Even if you took out the top people from these various fields, the people who were the bonds of the representatives of universities, I would not know them. I would know some of them but certainly not all of them.

Maybe one or the other name is known from literature but if one is confronted with that Gentleman it does not follow that one should know who he was. This tight connection which you are perhaps submitting here, never existed. One could almost say that, unfortunately, it never existed, for the big danger to German science and perhaps also abroad was that most people had a very poor eyesight in that regard and did not want to look right or left to see what happening. When science wants to advance it has to be able to see clearly.

Q: You have previously shown some knowledge of Beckenbach in connection with a cyclotron. Did you ever meet Beckenbach?

A: Yes. I met him on two or three occasions.

Q: Where did you meet him, do you remember?

A: I met him at Strasbourg — something that hadn't been quite finished yet. At that time I spoke to Mr. Steiner, Mr. Beckenbach, and with some physicist whose name I do not remember any longer. We discussed the problems at that time of research possibilities on a medical biological field.

Q: Was that in the fall of 1943?

A: That may have been at the end of 1943.

Q: Were you there with Karl Brandt? You remember he said he was there too.

A: Yes, I was there with him at one time. Yes, we looked at the institute where this cyclotron was to be installed. It was in one of the university clinics at Strasbourg.

Q: How many visits did you make to Strasbourg to see this?

A: I was in Strasbourg once in my entire life.

Q: Do you remember the other occasions when you saw Beckenbach?

A: I think I saw him in Berlin at one time and I think that was all. Otherwise I had no connections to him.

Q: Do you remember when that was?

A: I believed that was before I got there, that is, before I went to Strasbourg. Whether this visit was in connection with my efforts I do not know but nothing materialized anyway.

Q: Did you meet Hirt when you were in Strasbourg?

A: No, I do not know what Hirt looks like. I only know the —

Q: You say you met Dr. Stein there?

A: Yes, Stein was the dean at Strasbourg.

Q: Did you also see Haagen on that occasion?

A: No, I did not meet him.

Q: Did you meet a collaborator of Beckenbach — Dr. Fritz Letz?

A: I don't know that. There were two gentlemen there, some assistants, but whether a certain Dr. Letz was there I really don't know.

Q: What about Dr. Hellmuth Ruhl?

A: I can imagine nothing by that name but it is possible he was one of the gentlemen there.

Q: And you are sure that you know nothing about research by Beckenbach on chemical warfare?

A: No. No, we discussed the designation of a few atoms with regard to the radio-active manner and their mannerism in the human body.

Q: Well, but as I recall, Karl Brandt testified that on the occasion of this visit to see Beckenbach and the cyclotron, that he had some discussions with Beckenbach about his work in the field of chemical warfare agents and Beckenbach asked Brandt to help him and, as a matter of fact, he did help him, insisting, among other things, in setting up a laboratory at Fort Fransecky, just outside of Strasbourg. Did you know anything about that?

A: That discussions were pending in order to furnish a laboratory for this research work, I know.

Q: Do you mean to say you don't have any idea of what research work he was doing. It seems to me that if you were right there and heard him talking about fixing up a laboratory you would know what they were going to do with the laboratory.

A: I did not know that in detail. It did not concern me very much. One cannot ask me to know about every German lecturer and what he was doing in his institute. The situation was that all these lecturers and scientists were working on a number of problem simultaneously and were helped by assistants and interns and it goes beyond the strength of a human being to try to know all this and keep it in mind.

Q: But whether you know his work in detail or not, did you know that it was concerned with the field of chemical warfare?

A: I did not know that in that sense.

Q: I want to put a document to you to see if your memory will possibly be refreshed. I have handed the witness page 14 of Document NO-1852. It is on page 15 of the translation which has just been handed to the Tribunal.

A: This is a letter from Mr. Beckenbach. One cannot see on what date this letter originated; nothing can be seen here. It concerns Beckenbach's experiments on three cats apparently. That was with reference to aerosols. Aerosols in modern physics as well as in medicine in the future play the part of distributing the materials in a gas and also in the air. He says here that an aerosol was taken from hexamethylentetramine, the matter we usually call urotropin, and was neutralized by phosgene. That is what I can see from this report here. This letter is not directed to me and I can't remember ever having read it. This is in accord with what Dr. Brandt has testified; namely, that the work on chemical warfare agent was his affair and did not concern me.

Q: Well, now Herr Professor, this letter is addressed to the Fuehrer's General Plenipotentiary for Sanitation and Health, Surgeon General Professor Dr. Brandt, Berlin, Ziegelstr. 5-9, Surgical Clinic at the University. That is about two or three doors away from your office, in the same building?

A: Yes, that is correct.

Q: I assume that this letter came into his office sometime in 1944; don't you really think you read it?

A: No, I don't think so, and whether you believe me or not, you may rest assured that I was glad if my daily mail was not too extensive. We scientists have so much to read that we have no inclination to want to have this burden of mail increased. I cannot remember having read this letter.

Q: I will read the letter into the record. It is labeled "Top Secret (Military) 2 copies."

To the Fuehrer's General Plenipotentiary for Sanitation and Health, Surgeon General Prof. Dr. Brandt, Berlin, Ziegelstr. 5-9, Surgical Clinic at the University.

6th Report.

Q: The protective effect of an inhalation of hexamethylentetramine aerosol on phosgene poisoning.

A: Ten per cent. solution of Hexamethylentetramine is sprayed into a suitable box of 1/6 cbm with a Schlick jet. Aerosol of varying size particles is formed which is given to cats to be inhaled. Immediately after the inhalation they are placed in phosgene c.t. about 3000.

RESULTS

A cat inhaling aerosol on 3 different days for altogether 8 hours contacted a slight attack of pulmonary edema, survived; the control animal died after 6-7 hours of severe edema.

A cat inhaling for 2 hours also fell sick slightly and survived; the control animal died after 6 hours.

A cat inhaling for 1/2 hour fell sick severely and died after 20 hours of pulmonary edema, the control animal died after 6 hours. No further experiments could be carried on owing to lack of experimental animals.

So far as the small number of experiments permits of conclusions, the inhalation of aerosol from Hexamethylentetramine for more than 1/2 an hour has a working effect, if inhaled for more than 2 hours, it has a life saving effect."

/s/ Prof. O. Beckenbach.

Now, Professor, I want to show you another part of the same document. Now, will you turn to the second page of that, where you have the second report; do you see that?

A: Yes.

Q: This is also labeled "Military Secret," to the Chief Deputy of the Fuehrer for Medical and Health Affairs, Physician General Prof. Dr. Brandt. This is on page 2 of the English Translation, Your Honor.

Berlin, Ziegelstr. 5-9 Surgical clinic of the University. 2nd Report.

The subject of this report is "Investigations on the decrease in concentration of phosgene in the chamber used and its hydrolysis under the influence of atmospheric moisture." The first paragraph reads:

Before carrying out the planned phosgene experiments the chamber used needed to be examined to be draught-proof and the condition of the walls phosgene-proof. For this purpose continual readings of the phosgene content in the chamber atmosphere were carried out. We used WIRTH'S (1) method, whereby the chlorine formed by the phosgene are potentiometricaly titrated. Our experiences with this method are shown in a separate report by Dr. RUEHL.

I skip reading the rest of it, and go to page 3 of the English translation, page 3 of the original. The second paragraph reads:

In accordance with the Head-Physician (Oberarzt) Doctor WIRTH during his inspection of our institute stranger concentrations were then experimented with.

Witness, that indicates that Dr. Wirth of the Army Medical Inspectorate had looked over this laboratory at Fort Fransecky?

A: That is probably the case. It says so here. I don't know.

Q: Let’s turn to page 9 of the original, and page 9 of the English translation. You see, Witness, this is a series of seven reports. In order to understand them, we have to look at several of them together. We have here the fourth report, and from this, among other things, we are going to see the date, which doesn't appear on some of the other copies of those reports. This fourth report is dated Strassbourg, 11 August 1944; so I think we can probably assume that the fifth, sixth and seventh reports follow the 11th August 1944; and since Strassbourg fell, as I recall, sometime around September 1944, we can pretty well fix the dates of those subsequent reports, can't we, witness?

A: Yes, it can be assumed that the fifth report was made after the fourth report. I don't know exactly when that was.

Q: Will you be good enough to read this fourth report for us?

A: Yes.

Concentration of hexamethylentetramine in the blood and the use after intravenous injection and oral administering of diluted solution commercial tablets, and powders in capsules of pulverized substance.

When the protective effect of hexamethylentetramine against phosgene gas with human beings had been ascertained, beginning and duration of this effect were tested. From the outset, it was impossible to carry out this test by means of serial experiments on human beings. Assuming that the protective effect was a function of the concentration of hexamethylentetramine in the blood, speed and extent of the resorption and secretion of the protecting substance were measured.

The method chosen for the determination of hexamethylentetramine in the blood and in the urine will be demonstrated by one of us in a separate report.

After an intravenous injection of o,03 g/kg there occurs during the first minutes a considerable charge in the concentration as a sign of the incomplete mixture with the whole of the circulating blood as well as a quick decrease of the concentration to about 6 mg % during the first half hour. After 6 hours the concentration has decreased 2 mg %. The secretion is obviously a direct function of the concentration in the serum.

On oral taking of a diluted solution of about 10% hexamethylentetramine were traced regularly in the serum after 6 minutes.

The speed of resorption depends on the contents of the stomach. Shortly after a meal, resorption sets in later and is slower (curve 4), whereas on an empty stomach, Hexamethylentetramine can be traced in the stomach in quite a considerable concentration after 3 minutes (curve 5).

Psychological influences soon to play a role, too: In the case of curve No. ** which refers a nervous Russian prisoner of war, who could not be calmed down because of language difficulties resorption took place at a delayed rate. All the other curves show about the same course; quick increase to 5 to 6 mg.%, highest concentration after about one hour, a somewhat slower decrease to values of about 3 to 4 mg.% after 2 to 3 hours and then a slow secretion during 24 hours. Even after one day, traces of hexamethylentetramine can always be found in the blood.

Here, too, the secretion is in proportion to the concentration in the blood.

The diluted solution is out of the question for practical use in the Armed Forces. Therefore, the resorption of the urotropin tablets made by the firm of Schering was measured. These obviously firmly compressed tablets dissolve only slowly in water if not previously pulverized mechanically. Accordingly, resorption from the gastro-intestinal canal after taking the tablets is delayed. Curve 15 to 19 show the course.

Therefore, it was tried to compress tablets which dissolve more quickly. This problem, which is of importance for the practical use had to remain unsolved because of lack of a suitable machine for the manufacture of tablets and partly also because of lack of the necessary substances. We have therefore also measured the resorption of powder in capsules of the dried pulverized substance and have obtained curves whose resorption rate almost equals that of a diluted solution. It can be assumed that the same applies to tablets which dissolve quickly because they are mixed with starch or pectin. Finally it was tried to find out whether it is possible to obtain a blood level of about 2 to 3 mg.% in the serum with smaller doses of the drug, doing without the first steep increase of concentration. It has been proved that with a dosage of powders in capsule form of 0.015 g/kg body weight the individual range of fluctuation is considerable and that the desired concentration is not obtained in every case.

Summary

After oral administering of digestible doses of hexamethylentetramine (2 to 3 g) in a diluted solution and in powders in capsules the substance is traceable in the blood at the latest after about six minutes. In some cases, especially on an empty stomach, the protect substance can be traced in the blood already after 3 minutes. Its concentration increases within the first hour to a maximum of 5 to 6 mg% in the serum and decreases slowly in the course of 24 hours. The secretion in the urine is in proportion to the concentration in the serum.

Consequently it can be assumed that the protective effect against the inhalation of phosgene gas sets in about 5 minutes after swallowing the drug and that it reaches its maximum after an hour to one hour. Concentrations of 3 to 4 mg% remain in fact for many hours.

Strassburg, 11 August 1944 /s/ Dr. Fritz

MR. McHANEY: We would like the record to show this is in the fourth report and it was addressed to the Plenipotentiary of the Fuehrer for Medical and Health matters, Generalarst Proff. Dr. Brandt, Berlin, Ziegelstrasse 5-9, Surgical Clinic of the University, labeled "Top Secret (Military)".

THE PRESIDENT: Counsel should have this identified in some manner by some number.

MR McHANEY: If Your Honor please, for reasons which are satisfactory to the Prosecution, I have put the Document itself, which consists of some twenty pages in the original, in piece-meal fashion, but it all carries the same number, Document No. 1852 and will be admitted under one exhibit number. We will identify each report as it comes up, it is the fourth report on page nine of the English Translation. I will offer the document as a whole as seen as we have completed putting it to the witness.

Herr Professor, it appears from this fourth report that Dr. Bickenbach and his collaborator Dr. Letz were working on some Russian prisoners of war. You will see on the top of page nine of the original, where it say "Psychological influence seem to play a role", too: In the case of curve No. 12, which refers to a nervous Russian prisoner of war, who could not be calmed down because of language difficulties, resorption took place at a delayed rate. They could not even talk to the wretched Prisoner of War, could they? Can you tell from this report what were doing to him?

THE WITNESS: I believe, Mr. McHaney, that you over-estimate the dangerousness of this drug. Hexamethylentetramine you can buy in every drug store in America or Germany. For decades it was commercially sold and every man who has any bladder trouble knows these tablets and has to any during the course of a day. I myself worked scientifically on this question, which can be seen in Exhibit 4. Anything I wrote can be seen, but I don't remember all the facts.

I think that Bickenbach could have saved hinself this work, for it is generally known that hexamethylentetramine goes into the blood, as well as into fluid of the drain, that it goes from the gall bladder to the urine and these two peculiarities of this drug have led it to being used in bladder cases and also in the case of any inflammations of the brain. A number of people who received brain wounds during the war had to undergo treatment with the drugs for days. I think that three to six tablets are being mentioned here, I think I read it that the Russian Prisoner of War received six tablets of uretropin. Thousands of people used this druq in all countries

MR. McHANEY: Well, Herr Professor, what you say may be true, but I think I am being relatively calm under the circumstances. Isn' t it true that they were testing this drug, making preliminary tests if this drug with which they seen hoped be bring protecting against phosgene gas and were they not testing the drug on the Russian Prisoner of War?

THE WITNESS: That I cannot see from this report, but just a moment, let me look at it. On page 10 at the top, it says that after two to three hours traces of hexamethylentetranine can always be found in the blood. It also says that psychological influences seem to play a role, too and that the Curve No. 12, which is made available here, shows that in the case of a Russian Prisoner of war psychologically impressed by the taking of this drug and the resorption took a different course in other cases. Maybe I could ask you to show me the curves, then I could be more about it, but there is nothing else I can say from the report here.

MR. McHANEY: Well, Herr Professor, look at the paragraph of the report, that will show you what they were doing and why they were testing this drug, consequently it can be assumed that the protective effect against the inhalation of phosgene gas sets in about 6 minutes after swallowing the drug and that it reaches about this report is the appearance of the Russian Prisoner of War in Fort Vonsek and Herr Professor because I have read the seventh report, which is an page 16 of the English translation.

Does the Tribunal wish to adjourn before I read this? I might say to you, witness, you may possibly read this report during the recess. I think you will find from it that they carried out experiments on forty prisoners, which from the fourth report we assume to have been Russian Prisoners of War to when they could not even speak. If you will read the appendix carefully to this seventh report, you will see that they killed seven of them with phosgene gas.

THE PRESIDENT: The Tribunal will be in recess.

(A recess was taken.)