1947-05-02, #2: Doctors' Trial (late morning)

THE MARSHAL: Persons in the courtroom will please find their seats. The Tribunal is again in session.

THE PRESIDENT: Are there any further questions of the witness by defense counsel? There being none, the prosecution may cross examine.

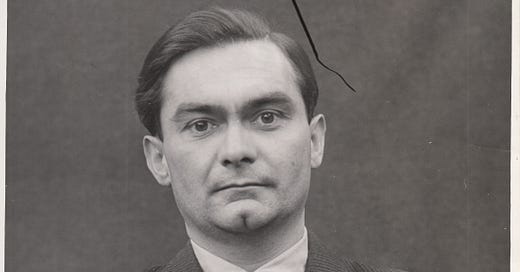

DR. HANS ROMBERG — Resumed.

CROSS EXAMINATION

BY MR. HARDY:

Q: Dr. Romberg, where did you study medicine, doctor?

A: Berlin and Innsbruck.

Q: Were you ever in the Wehrmacht?

A: Yes, in 1936 end 1937, that is, December 1936 to January 1937 I had two months basic training in the Luftwaffe and then two periods of additional training so that at the beginning of the war I was an Unterarzt [junior doctor] in the reserve.

Q: When were you first assigned to the German experimental station for aviation, the DVL?

A: I never was in an experimental station but from 1 January 1938 I was in the DVL in Adlershof.

Q: Was it because of your position in the DVL and your work in the field of aviation medicine the reason why you were not in active duty with either the Luftwaffe or some other branch of the Wehrmacht?

A: Yes, I was declared essential for that agency, the DVL, so that I could serve in the DVL during the war.

Q: Well now, you have expressed here in the course of your direct examination by virtue of some affidavits which you have introduced in evidence that you were an anti-Nazi. Is that the impression you want to create upon this Tribunal?

A: I didn't ask for these affidavits, rather they were sent to me so that I had no influence on the way these affidavits were expressed, particularly the Jewish one from Berlin.

Q: Were you a member of the Nazi party, doctor?

A: Yes.

Q: When did you join?

A: 1 May 1933.

Q: You joined very early, didn't you?

A: That was the time when quite a number of people joined the party, right at the beginning. I was a student at Innsbruck at the time and joined on 1 May 1933.

Q: Was it to your advantage during the course of the time you were a student to be a member of the Nazi Party?

A: No, it had no influence on my studies.

Q: You joined by choice?

A: At that time I thought that good would come of it.

Q: Now, doctor, you have stated here on direct examination the first time you heard about the experiments to be conducted at the Dachau concentration camp was when Ruff informed you he had a visit from Professor Weltz, is that correct?

A: Yes.

Q: After Professor Weltz paid a visit to Ruff, how extensively did you and Ruff discuss the visit of Professor Weltz?

A: That lasted a half an hour or perhaps as much as an hour for sure.

Q: At that time was it established that the concentration camp inmates were to be subjects used in the experiments?

A: Yes, as I recollect, that was already said in this conversation.

Q: Then it is true that Professor Weltz informed Ruff that it was the plan to conduct these experiments at Dachau on inmates of the concentration camp?

A: Yes, that was essentially the contents of that conversation between Weltz and Ruff.

Q: Well then, in a matter of a few days you and Ruff proceeded to Munich for a conference, is that correct?

A: Christmas intervened there, so probably it was about a month later when that trip took place.

Q: Now, when you arrived at Professor Weltz's institute in Munich, you found Rascher present, is that it?

A: As I remember, he wasn't there at the beginning. He came later. We arrived first.

Q: And that was the first time you ever met Rascher?

A: Yes.

Q: Did you discuss among yourselves at that time — that is the conference wherein Weltz, Rascher, Ruff, and yourself took part — the purpose of these experiments?

A: Well, the purpose was also discussed although it had already been established before that on the basis of the decision and we went to Munich in the first place to carry out these experiments.

Q: Well now, in this preliminary meeting what was the point which you were trying to establish? Was it research into high altitudes above 12,000 meters?

A: It was the pressing program of finding out how to rescue people from those altitudes.

Q: And this would be the first time in this particular field that such research was to be conducted, is that it — that is, higher than 12,000 meters?

A: No, we had already gone higher at a slower descent from 15,000 and a rapid descent from 17,000, not only we in our institute but also other institutes in Germany had already done this.

Q: And then, of course, the all important problem came up at this discussion in Munich that the inmates of the concentration camps would be used, and now you state Rascher had a letter from Himmler granting him authority to carry out these experiments at the Dachau concentration camp and to use the inmates therein. Would you kindly tell the Tribunal as much as you can remember just what this letter said?

A: I can't say for sure any more now. Rascher read it aloud to me. Roughly it said that the approval in principle for Rascher to carry out the experiments in Dachau was still given and that criminal prisoners were to be used who volunteered.

Q: Did it contain the words "criminal inmates would be used and that the inmates were to he volunteers"? Did it specifically state that in Himmler's letter?

A: "Criminal inmates" was certainly not in the letter but the word "criminal" was in it.

Q: Was the word "volunteer" in it?

A: Yes, that word was in it.

Q: Go on. What else did the letter contain?

A: I don't believe there was much more in it. There was some notice that other offices were to be informed and then there was the signature.

Q: There was definitely a pardon clause contained in Himmler's letter, was there?

A: Yes, that was in there.

Q: Well now, these experiments that you were conducting were to he in an altitude higher than 12,000 meters, and I call your attention to the fact that Dr. Ruff said that in Berlin they had only gone up to 12,000 meters, that is, prior to the Dachau experiments, so far as his particular research was concerned. Wasn't it a very dangerous situation, one wherein it would be difficult, more than difficult, to receive volunteers?

A: First of all, I don't believe Ruff said here that they had gone only to 12,000 meters because he knows very well that we had conducted experiments at higher altitudes at the Institute and that he had participated in them. I don't remember what his precise words were, though. You never know ahead of time how dangerous such experiments are going to be. That was the case, also, with our own experiments. It was a further ascent such as was gradually taking place in aviation regarding speed and altitude and the size of the machines, etc.

Q: Well, now, what was the date of this Himmler letter? Do you recall?

A: No. I don't know the date. It was certainly in the year 1941, before the conversation.

Q: And you were sure that Himmler specified persons to be used to be volunteers?

A: Yes.

Q: Well, now, who requested Himmler that subjects be set aside for the high altitude experiments?

A: These negotiations had taken place before, between Rascher and Himmler. We didn't know the details. Rascher, however, showed us through this letter that he had permission and plenipotentiary powers from Himmler.

Q: I see. Well, now let us turn to page 53 of Document Book No. 11, which is Document No. 1602-PS the fifth document in the book. This is a letter from Rascher to Reichsfuehrer SS Heinrich Himmler, dated 13 May 1941. I ask you now to refer to the second paragraph. I will read from it:

For the time being I have been assigned to the Luftgaukommando [Air District Command] VII, Munich, for a medical course. During this course, where researches on high-altitude flights play a prominent part (determined by the somewhat higher ceiling of the English fighter planes), considerable regret was expressed at the fact that no tests with human material had yet been possible for us, as such experiments—

Does the interpreter have the letter, Document No. 1602-PS, 53 of the English.

I am starting with the second paragraph.

Do you have the Document Book No. II?

INTERPRETER: The texts don't seem to correspond. If you will read slowly the interpreter will keep along.

MR. HARDY: Well, there only three sentences in the first paragraph. It begins with the fourth sentence. It begins:

For the time being I have been assigned to Luftgaukommando VII, Munich, for a medical course.

Do you have it, Mr. Brown.

INTERPRETER: Texts don't correspond in German and English.

MR. HARDY: Well, they corresponded before, Mr. Brown, some three or four months ago. It is obvious that you have the wrong book then.

INTERPRETER: I have 1602-PS, on page 53.

MR. HARDY: That is right— the letter. I will read the entire letter; then maybe it will help you. "1602-PS." Do you have the letter in the German book?

Dear Reichsfuehrer. My sincere thanks for your cordial wishes and flowers on the birth of my second son. This time, too, it is a strong boy, though he has come 3 weeks too early. I will permit myself to send you a picture of both children at the opportune moment.

For the time being I have been assigned to the—

THE INTERPRETER: At this point the texts deviate from one another.

MR. HARDY: Well, we will go back to that. Will you please check that immediately? We will go back to that at a later date. It is important that you check it immediately, please.

DR. VORWERK (Counsel for the defendant Romberg): Mr. President, in the German Document Book II, page 54, there is in this document, the part that the prosecutor wishes to read is designated as "illegible."

In other words, it is not contained in the German document book.

THE PRESIDENT: Counsel, is the photostat of the original available here?

MR. HARDY: No, Your Honor, that is in the hands of the Secretary-General.

THE PRESIDENT: Well, the Secretary-General will please bring to the Prosecution, a part is obviously not contained in the copy of the document book which is in the original.

DR. VORWERK: Now, if this part is subsequently to be put in, this would, in effect be submitting a new document. Therefore, I request that the prosecutor be instructed to show us this document twenty-four hours before he wishes to put in evidence.

MR. HARDY: Of course, in cross-examination I don't have to follow that rule. May I ask the court reporter to kindly read the next sentence after the first paragraph where I stopped reading and it becomes incoherent to read in the next sentence? Pardon me—the German; contained in the German document.

INTERPRETER: In the German book, this is the word —

MR. HARDY: All right, what comes after that — the first full sentence that corresponds is the sentence in German, and that corresponds in the English document book—about three-eights of the way down the page:

The experiments are made at Permanent Luftwaffe Testing Station for Altitude Research—

that sentence is in the eight line of the second paragraph.

INTERPRETER: (Reads from German text)

MR. HARDY: I will proceed, Your Honor, and wait for the original exhibit. Of course, in this discussion, Your Honor, the Defense counsel must bear in mind that this document was presented to him—a photostatic copy thereof—and will be the same as the exhibit, whereas the document book may well have that marked "illegible." He has had a photostatic copy of this document—as it is in evidence—since December the 4th, 1946.

THE PRESIDENT: The Tribunal is much interested, of course, in the accuracy of these document books. They desire to have that matter carefully checked.

BY MR. HARDY:

Q: We will go back to that point, Dr. Romberg;

Now, after Dr. Rascher has exhibited the Himmler letter to you which indicated subjects to be used, must be criminals, and that they must volunteer. Did you after that time positively establish that each subject used was a volunteer?

A: You mean later, when the experiments were actually carried out?

Q: Yes.

A: With the experimental subjects for our experiments—I had talks at some length during the course of time—and they corroborated that.

Q: Well, now, you have testified that you used some ten to fifteen experimental subjects in experiments over which you and Ruff had some control. How long did you use these ten to fifteen subjects?

A: Throughout the whole course of the experiments; they were available for the experiments and were used in them.

Q: In other words, you had those subjects available from—according to your own testimony now—the twenty-second of February until the time that the experiments were completed—which you say was about the twentieth of May?

A: Yes.

Q: So you had them the whole month of March, April; nearly the whole month of May. That was ten to fifteen subjects. Is that right?

A: Yes.

Q: Did you talk to each and every one of those ten or fifteen subjects?

A: In the course of time I spoke personally with all of these men on all sorts of subjects; on their having been sentence, on what their previous sentences had been, on their position in the camp, and why they had volunteered for the experiments.

Q: How many times was each subject of this small group submitted to an experiment—or subjected to an experiment?

A: I should say about twenty—for each person.

Q: Twenty times each person went through an experiment! Well, now, in the course of nearly three months you subjected each one of these subjects to perhaps twenty experiments apiece. Now, kindly, for the Court record, give us the names of some of these subjects. You must have well known their names after working with them for such a length of time as that. How many names can you remember?

A: There was a men named Rockinger.

Q: Spell, that please.

A: R O C K I N G E R

Q: Do you know his first name?

A: No, I don't

Q: Know where he was from, what his home city was, or anything like that?

A: No, I don't know that now either.

Q: You tell me you experimented on a man twenty times and you don't even know his first name, don't know where he is from, or anything about him?

A: We didn't talk about each other's first names nor about these details. It is possible that I did find out then where he came from and what his first name was, but I have forgotten it by now.

Q: Well now, can you give us the names of any of the others? It shouldn't be too difficult. I think I could remember the names of ten or fifteen men I worked with for such a time as that, on such an important problem.

A: There was a man named Sobotta.

Q: Spell that, please.

A: S O B O T T A

Q: Can you give us any further information about him?

A: Sobotta occupied a special position there, because he was the man who went through the most experiments, and at the same time had a sort of superior position inside that group, and I think Sobotta was the man I talked with most of all. Consequently, I can say regarding him that he was a safecracker. He broke into a large Austrian State bank, among other things, and, so far as I know, he was an Austrian

Q: Well now, do you know the names of any of the others?

A: Yes, I remember a man Kloos and the name Zoslak or something like that. Kloos is spelled K L O — or O O — S, and the other, Z O S L A K, or something of that sort, I don't know that for sure either.

Q: Well now, don't you know any particulars about these men? It seems to me that you quite frequently, in the course of the experiments, after the men were unconscious and after they came to, you would ask them questions like the delicatessen dealer. It would seem to me that you would have gained more information about those men than you have during the course of the experiments. Don't you have more information about them to give us so that perhaps we can find them? Do you know where they are?

A: No, I have no idea.

Q: Did any of them survive the experiments?

A: All survived the experiments. The witness Vieweg has corroborated that among others.

Q: And they were volunteers?

A: Yes.

Q: Yet you haven't found any of them and brought them here before this Tribunal?

A: How am I to find these men when I am interned?

Q: Your defense counsel could well put out a notice and look for them. If we could get the information, perhaps we could find them. Perhaps you can remember the first name of Sobotta? Do you remember that? This is the man you talked to the most.

A: No.

Q: Don't remember him?

A: No. I certainly don't remember his first name.

Q: Now, what was the reward that those volunteers were to get for being subjected to the experiment?

A: What they actually received as a reward, I don't know for sure. I know only from the documents here that Sobotta was released, and I know that he had theretofore been promised that he would be pardoned and that Himmler had personally verified this when he paid his visit there. Then Himmler, when the report was made at the conclusion of the experiments, said it again, and Rascher also said that they were to be set at liberty.

Q: Do you remember the name Sobotta from those documents, or did you remember it from your conversations with him?

A: I remembered it from our conversations. Particularly, because a University professor at Bonn had the same name and that is why this rather unusual name stayed in my memory.

Q: Well, of course, when you remembered the professor at Bonn with the same name, you must certainly have asked the fellow "Are you any relation to him?" That is a likely question, wouldn't it be?

A: I don't know whether I asked that or not. In principle, the fact that a University professor should be a relative of a safecracker is not too probable, but maybe I did ask him, it is possible.

Q: You didn't find out from that course of questioning whether or not the fellow came from Munich, Berlin, France or where, did you?

A: As I have said, in the case of Sobotta, I assume that he was an Austrian.

Q: Well now, I have assumed here all along that you were perhaps a thoughtful physician and apparently a very conscientious research worker. It seems most unusual that a man of your caliber didn't have enough interest in the people that he was subjecting to experiments to have more information about them than you have. Didn't you care? You say, you tell us here, that you asked them whether they were volunteers. Did you just says "Are you volunteering", and not ask them any further questions? You weren't interested? It seems strange for a physician not to be interested in some of the background of the people that he is subjecting to experiments. Even Dr. Ding know some of the people that he was using in his experiments in Buchenwald.

A: As I said, I did talk with these people. Moreover since I associated with them for two or three months during these experiments and put them in the experiments and saw what they had to do, there is no doubt in my mind at all that they were volunteers. When I asked them questions, I didn't ask then in a critical spirit because I had any mistrust of them, but these questions I asked simply occurred in the course of the conversations I had with them.

Q: Well now, Doctor, Walter Neff's job there was more or less taking care of these experimental subjects, wasn't it? Wasn't he the block elder?

A: Neff was the block elder for this group, yes.

Q: Well now, he was in a position to know more about those experimental subjects than you, wasn't he? He perhaps had a card index file on them.

A: No, I don't believe he had a card index file.

Q: Well, he knew more about them than you did, didn't he? He lived with them. He was another inmate.

A: That's possible. I don't know how well he had known them before or how well he made friends with them. That, of course, I can't judge.

Q: However, you would be willing to admit that perhaps his testimony concerning these subjects is more reliable than yours?

A: I can't judge as to the reliability of Neff's testimony. I just don't know.

Q: Well now, these ten or fifteen — Neff referred to them as "exhibitionists" or "exhibition subjects". Do you recall that?

A: It was Vieweg who used that term for the first time here — "exhibition subjects."

Q: Well now, Neff stated that ten inmates had volunteered, didn't he?

A: Yes.

Q: As a matter of fact, he stated, that's on page 614 of the record, Your Honor. Well now, he also stated that only one of the subjects used in the experiments was released, didn't he?

A: Yes, that's what he said.

Q: The documents support his testimony, don't they?

A: Regarding Sobotta, he is specifically mentioned for pardon in Brandt's letter or Rascher's.

Q: Well now, do you recall Neff stating here that he remembers the first days of the experiments when they had the first series of experiments, and that he stated that Ruff and yourself were present? Do you recall that?

A: First, he said that Ruff was present on the first day in Luftwaffe uniform. Later, he corrected himself and said he was not in Luftwaffe uniform, and it wasn't on the first day either. Rather, he was in civilian clothes and it was a couple of weeks later.

Q: Well now, tell me, in these first series of experiments did you use these ten or fifteen men that you had at your disposal?

A: Yes.

A: Page 622 of the record — Walter Neff, a man who lived with these gentlemen, who was the block eldest, who knew who was going in and out of the low pressure chamber, stated that no deaths had occurred in this first series on that day, but this first series of experiments was not carried out on the volunteers? Do you remember that?

A: Neff said here that all those ten or fifteen men were not volunteers at all. I remember that very definitely and he also said that there were no fatalities. Not during the first few days, but I think he said during the first few weeks.

Q: He also said that these volunteers were political prisoners, didn't he?

A: Neff said here that all sorts of people were there — all classes or strata that you can imagine.

Q: Well now, when you made your plea or Rascher made his plea to secure the volunteers for these experiments, what form or in what manner did he appeal to the inmates of the Dauchau concentration camps?

A: Just how he did this I don't know. This was not done by Rascher, but by the Camp Commander on the basis of the discussion of Rascher's letter and the information given by the adjutant Schnitzler, from Munich, who was present at the discussion. As far as I know the people were asked at the roll call who wanted to volunteer and then a great number of volunteers —

Q: Now, you say roll call, do you mean roll call of only habitual criminals or criminals condemned to death because you only used criminals in these experiments, or did the roll call consists of all sorts of prisoners, political prisoners and everyone else?

A: Just how the roll call works I don't know, or whether a specific group was established a priori.

Q: You actually don't know very much about this, do you?

A: I had nothing to do with selecting them. There was a clear cut agreement with the camp commander which had been reached during this discussion. He had said that we would find enough, and told Rascher that he could pick the people who were physically qualified for the experiments.

Q: Now, what did you offer them as an inducement to undergo these experiments; that was the inducement, wasn't it, offering them a pardon if they successfully underwent the experiments?

A: I didn't offer them a pardon. I wasn't in a position to do that.

Q: You must have insisted before you worked on them that they were to be pardoned, that is the gist of the testimony, you would not use men who at least were not offered a pardon after you had experimented on them, would you? I am sure you wouldn't, would you, Doctor?

A: That was a clear cut statement, also that the people should be pardoned and that their sentences should be reduced. This was not simply a theory, but was set down in writing, and Himmler had made the same promise when he was there.

Q: Of course, Himmler's idea about pardoning these men wasn't as conclusive as you stated, was it? You state in the original Himmler letter that Himmler was in favor of pardoning all the habitual criminals that were subjected to these experiments; now, did Himmler have a change of heart and later withdraw that promise, or what happened?

A: He didn't take anything back, at least I didn't know it if he did, but of course, I can't check whether or not he kept his promise. I can't force a man like Himmler to keep his word, more over at that time I had no reason to believe that this was a promise that was not to be kept.

Q: Well, now, when these volunteers, so to speak, did volunteer, were they warned of the hazards of the experiment?

A: They were not just 'so-called' and I can say that they were really volunteers. I told them what the point of these experiments was, what they had to do, what they had to particularly take care of, and just what their active participation as experimental subjects was to be.

Q: Well, now, you must have told them that these experiments, gentlemen, you are going to go through are painless and they won't be harmful at all, you may go through some distortions, however, at that time you may be unconscious. When you wake up you won't realize you have gone through experiments; there is no danger of death, and that the purpose of this experiment is to benefit the German aviators, something to that effect; you must have said something similar to that to them?

A: Something similar, not in detail as you have said it.

Q: I should think you would have done it more in detail than I have, because I am no expert on that subject as you are?

A: I have already explained to them what altitude sickness is, explained what that they would became unconscious and this was the most important point, after waking up so far as they are clear in their minds they should pull the parachute release.

That was the most important thing, of course, and I also knew very certainly I also told them that these were experiments in which nothing would happened as far as man's judgment goes.

Q: In other words, you impressed upon them that these experiments were harmless?

A: I told them that to the best of our ability we would see to it that nothing happened to then. I also told them there was a certain risk involved which could not be precisely calculated, but so far as the physicians were concerned they would see to it that nothing happened to these people.

Q: Well, now, Doctor, if that was the case, in the course of these high altitude experiments why was it necessary to use habitual criminals and criminals condemned to death; in other words, why was it necessary to offer that particular group of individuals an inducement to undergo such harmless experiment; why couldn't you as well call in the political prisoners and have said, "Gentlemen, we have an experimental program here", and explain to them how harmless the experiment is, and "if you will undergo the experiment we will give you one more loaf of bread than you are getting or one more piece of sausage a day," which giving to them would be quite an inducement, whereas you used criminals, which as you say were justifiably placed in concentration camps and were a menace to the public, because they were criminals, and now you are going to subject them to a perfectly harmless experiment and allow them to go out into the public and commit some more crime; it doesn't seem logical if it is a harmless experiment; there must be some danger to it?

A: As to what group of subjects were to be chosen as experimental subjects I had no influence. Himmler as Reichsfuehrer SS and Chief of Police issued the directive. We had no influence on that. That is true of the case of doctors all over the World, the doctor doesn't choose the people, the State does?

Q: That is right. I am going to refer to it. I hope this is in order so we can read it, page 62, Document Book 2, Document 1971-PS. This is the Himmler letter to Rascher in answer to Rascher when Rascher sent in these preliminary reports. This is where Himmler says they shall be pardoned to a concentration camp for life. This is dated 13 April 1942.

Dear Dr. Rascher:

I want to answer your letter with which you sent me your reports.

Especially the latest discoveries made in your experiments have interested me. May I ask you now the following:

This experiment is to be repeated on other men condemned to death.

I would like Dr. Fahrenkamp to be taken into consultation on these experiments.

Considering the long continued exploited in such a manner as to determine whether these men could be recalled to life. Should such an experiment succeed, then, of course, the person condemned to death shall be pardoned to concentration Camp for life.

That was pretty white of him, wasn't it? That is quite a pardon to give a man, isn't it? After you practically kill him you can recall his life and if you are successful in recalling him to life then we will pardon him not to go scott free, but to a concentration camp for life, that being all the evidence we have of pardon from Himmler, isn't it?

A: I did not make the experiments. I did not get the orders from Himmler to carry them out.

Q: You firmly indicated the attitude Heinrich Himmler had as to pardoning concentration camp inmates who had been condemned to death; he doesn't even mention habitual criminals who have not been condemned to death, that is his attitude.

I think it is exemplary, isn't it?

A: I don't knew just what the general procedure was with pardons in such cases as this. In general people condemned to death are happy if they are pardoned just as long as they don't die; now whether a person condemned to death could be set scott free I don't know, I can't judge. However, this was Himmler's directive. It was sent to the necessary offices, to the Chief of the Sipo, Gluecks, and so forth, and here it says people condemned to death are to be pardoned to concentration camp for life.

Q: Now, in the course of your experiments you only used so you and Ruff say, from 10 to 15 experimental subjects, all volunteers. Was it made clear to this group of experimental subjects, that is the one in the Rascher experiments and the one in the Ruff-Romberg experiments, and according to Ruff that numbers in the hundreds and up to 80 were killed eventually in high altitude experiments. Now, was it made clear to these subjects when they volunteered for experiments what they were volunteering for; did the subject know whether or not he was volunteering for the Ruff-Romberg or Rascher experiment, or merely for the Rascher experiment; how did he know when he got into the experimental chamber who was going to work on him, how did he know that?

A: Our men lived at the station and carried on the experiments continuously, and I told them exactly what experiments were to be carried out and to what purpose they served. The other experimental subjects whom Rascher used, I had nothing to do with. Neff says they were brought to the station with SS guards of some sort and that Rascher then carried out the experiments with them.

Q: Well now, Doctor, each and every time an experimental subject entered the low pressure chamber, did you look at him and make sure he was one of your ten or fifteen?

A: If these were my experiments, then I usually called the people myself in person, and said whose turn it was. I had a list to see that the experiments were evenly divided among the experimental subjects.

Q: Well, you took a list; what did you call them; numbers one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine, ten; or did you call them by names?

A: The names were there.

Q: You only remember three names and you used to call them by name?

A: I remember four names.

Q: Four out fifteen and you used to call these men by name and make sure, one would not have twenty times in the chamber and the other five; you wanted them to file in evenly, yet you can remember only four names of such an important project.

A: That was five years ago and I carried out so many experiments during that time at Dachau and was in the office too, I cannot tell you the names of the people at the institute either.

Q: Yet, whenever a person entered that experimental chamber, you knew whether or not it was one of your men?

A: Yes, I knew that.

Q: And you checked up each and every test on these individuals and made sure that a wringer was not wrong in on you; did you?

A: I knew who these men were.

Q: Well now, what is your moral attitude, Dr. Romberg, as to the capacity of a prisoner or a person incarcerated to volunteer for an experiment? You have heard here at this Tribunal, some say that a prisoner could not volunteer for anything, some think he could and some think he was coerced. What ever the situation may be, what is your attitude concerning the capacity of a person incarcerated to volunteer for a medical experiment.

A: May I go into this in some detail?

Q: Certainly.

A: First we must discriminate in principle between what the state does and what the Doctor does. That the state can take criminals condemned to death and make them available for experiments and does so —

Q: Doctor, just a moment. Please, before you go into the attitude of the state and the doctor, let us go into this phase, whether or not a person incarcerated in prison can himself, of his own violation, volunteer for an experiment, regardless of state laws or of doctors. Do you think when a warden of a prison or a concentration camp commandant comes up to an inmates and says, "Will you volunteer for this experiment?" do you think he conscientiously volunteers; what is your attitude on that? You have heard it in the courtroom, you have heard three or four versions; now I want to hear your version.

A: Yes of course. It is my view that we must discriminate between the philosophical freedom of determination and actual freedom of determination. The philosophical freedom of determination, I don't know anything, nor does anyone else know of freedom determination. Then we arrive at a decision, there is no such thing as philosophical freedom. The person, of course, is also not free in the use of his will, but on the other hand, he is completely free in his choice between the various possibilities that he is confronted with.

For instance, if a man is condemned to death, he goes back to his cell and finds a letter saying that if he volunteers for an experiment that is dangerous to life, he will be pardoned. You don't have to issue an order for him to do this. He is perfectly free to accept his death sentence or to go through the experiment. This is, of course, an extreme example.

Another example is a man sentenced to a long term who volunteers for malaria experiments, he is asked also, if he wants to volunteer and he can make a perfectly free choice. He is condemned to ten years imprisonment, he has the choice, does he want to accept the future of malaria, or ten years in prison.

Within this possibility, he is perfectly free in his decision. That the situation exercises certain coercion on him, is quite clear. That is nothing unusual as far as the doctor is concerned. I have already said that the state apparently recognized the fact that a person can volunteer, because all over the world it has given prisoners a chance to volunteer.

The second question is what is the doctor's position? He always says the state is the law and secondly, the doctor is perhaps more accustomed to formulating a decision, when there is a coercion element in the situation than other people. He is inclined to regard such conditions as voluntary conditions. For example, decisions for women in child delivery are made in event of a caesarean operation. The doctor does not arrive at that decision because he wants to, but because the situation makes it necessary. He has to confront himself with the problem, perhaps if I should let it be a natural birth it will be successful and perhaps not. He has to draw his own conclusions in this situation. Perhaps if a person is wounded and says I was asked at that time whether I wanted my arm to be amputated or not and I said I don't want it to be amputated and you can see now I have my arm. Undoubtedly there are such cases. The doctor has to say honestly to the patient that in his knowledge and to the best of his knowledge your life is in danger, if we don't amputate this arm. Now, make up your mind, if we don't amputate, you are in great danger, if we amputate you are bound to recover, but you won't have one arm. Now, from the tale told by this man, who did not permit the amputation, we know that, and there are some people who desire to let the amputation take place and some people who desire not to, they are in a situation, where by fate they are under coercion. Fate has placed them in this situation, and it is one which the doctor is more familiar with, because again and again comes upon such patients.

THE PRESIDENT: Counsel, we will suspend the examination at this time for a moment. The Tribunal would like to examine German Document Book 2. Will counsel hand a copy to the Tribunal?

MR. HARDY: I will check my files on this Document. It may be that one of the photostats are missing.

THE PRESIDENT: The Tribunal desires to examine that Document book.

JUDGE SEBRING: Mr. Hardy, would not the official text of the document, as it appears in the record of the International Military Tribunal Trial disclose the status of this.

MR. HARDY: That may not have been used before the I.M.T., I am not sure, Your Honor. It has an I.M.T. number, I don't know, whether it was used or not, can you ascertain that?

JUDGE SEBRING: They quote on the Niebergall affidavit here, "I certify that Document No. 1602-PS was introduced into evidence as Exhibit No. U.S.A. 454 in the Trial by the International Military Tribunal of Hermann Goering, et al."

MR. HARDY: I will check the original in the I.M.T. file.

JUDGE SEBRING: U.S.A. 454.

THE PRESIDENT: This document, as it appears in the German document book, varies greatly. There is more text in the German than in the English document book. They do not correspond. Now the photostat as returned here manifestly, contains much more text than appears in the English document bock. The English opens with a short paragraph of four lines, then follows a long paragraph and then two very short paragraph. Now the photostat shows either three very long paragraphs or two long ones and two short ones. Now, the certificate, attached to this document in the English document book, certified that the English translation is a true and correct translation of the original document, which it manifestly is not. The first page of the photostat shows double printing, what happened, I cannot tell, the double printing is there together with a white blur, which makes part of it illegible. Now this document, according to the certificate attached thereto, was admitted before the International Military Tribunal.

MR. HARDY: It appears there are obviously two different documents, your Honor, I will have it checked in my files and the files of the International Military Tribunal and I will try to report on it at 1:30 if I can do that.

THE PRESIDENT: The Tribunal is much interested and is quite dissatisfied that we have in our document bock a manifestly incorrect translation of an important document, together with a certification that it is true and correct.

MR. HARDY: It is surprising to me that this was not noticed as this document was placed in its entirety into the record.

THE PRESIDENT: This is a peculiar circumstance, the Tribunal is confronted with. I will return the German document and original photostat and counsel will make an investigation of the result.

The Tribunal will be in recess until 1:30 o'clock.

(A recess was taken.)