1947-06-14, #2: Doctors' Trial (late Saturday morning)

THE MARSHAL: The Tribunal is again in session.

THE PRESIDENT: Defense Counsel may proceed.

BY DR. SERVATIUS (Attorney for Defendant Karl Brandt):

Q: Witness, yesterday you testified that voluntary consent is the first prerequisite for human experimentation. Previously you had said that you yourself had been reluctant to apply for volunteers; is that so?

A: No.

Q: Didn't you say just now that you didn't want to ask your students to volunteer but left that to other agencies so that your authority might not constitute some form of coercion?

A: Yes, that is insofar as my personal direct request to the individual is concerned, I thought, because of my position as a professor, it might unduly influence the student to say yes.

Q: You were probably of the opinion that your authority might persuade him to do something that he otherwise would not do.

A: Yes — through individual contact.

Q: I say, Professor, don't you know that in general the volunteer aspect of the person's consent has been under suspicion?

A: I don't understand that question. Will you repeat it?

Q: Is it not so that in medical circles and also in public circles that these declarations of voluntary consent are seen with a certain amount of suspicion; that it is doubted whether the person actually did volunteer?

A: Can you be more specific?

Q: In your commission you probably debated how the volunteers should be contacted; is that not so?

A: Yes.

Q: On this occasion was there not discussions of the question that you should assure yourself that no coercion was being exercised, or that the particular situation to which the person found himself who applied was being exploited?

A: Yes, I was concerned about that question.

Q: There were discussions about that?

A: Not necessarily with others, but there was always consideration of that in my own mind.

Q: Witness, a number of documents were brought forth yesterday, Friday, from which it was to be seen that volunteers did volunteer, for instance eight hundred or more prisoners applied for a malaria-experiment; and there was a radio report; all of these persons had a motive for declaring themselves ready. What are the motives of a prisoner that persuade him to volunteer?

A: These prisoners said they volunteered in order to help people who might have malaria.

Q: In this report the individual persons were asked, five or six of them were — one says that he has volunteered because he is condemned to life imprisonment, and he has applied to oblige the army. Another says that he is doing it because his brother is a soldier on the front and has malaria. And another one says — two of my brothers in the army had malaria; and a third one says in the last war —

MR. HARDY: Dr. Servatius refers to Prosecution Exhibit No. 519 for identification, and request that he supplied the passages so that Dr. Ivy can properly testify.

BY DR. SERVATIUS:

Q: Witness, from this radio report I shall read the answers of the experimental subjects to you. One Mr. Quall is asked and he says:

I expect Captain Jones, that these men have many reasons for their volunteering for this war.

Captain Jones: Yes, they have. Many have sons and brothers in the armed services, other have other patriotic motives, but I am not the one to tell about them.

Quall: I get the point.

Capt. Jones: With the permission of Warden Rangen we are going to talk to several of these volunteers right now. Here is a man who is older than some of the others. What is your name?

Johnson, I am George Johnson—

— number so and so.

Quail: Johnson, I have heard you have a pretty high fever as a result of those tests.

Johnson: That is right; at one time my temperature was 104 degrees.

Quail: 108 degrees, and you are here to tell the story.

Jones: What was your main reason for volunteering for these tests.

Johnson: I served in the U.S. Army during the first World War, and here by going through with these tests I helped some of my buddies in the war just ended.

Quall: Thanks, Johnson. Now, here is Charles Eirtz,—

— number so and so —

Eirtz: My brother was killed in the crossing of the Saar River; that made up my mind for me; we weren't being shot at here; it was the least we could do.

Quail: And here is George Storm; George Storm,—

— number so and so.

Storm: Two of my brothers in the service caught Malaria, If I can help the army, I can help my brothers.

Quall: Here is a man who is one of the many inmate nurses helping out in the war. What is your name?

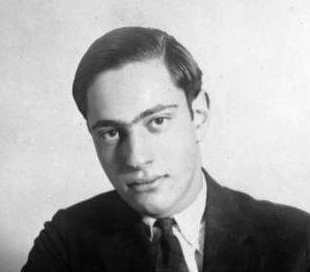

Leopold: Nathan Leopold,—

— number so and so.

I was a malaria volunteer, and now I am acting as a nurse.

Quall: How do most of the patients react under these tests?

Leopold: All the men are good soldiers; their morale is high.

Quall; Now, two inmates who are no strangers to malaria —

Walker: My name is George Walker,—

— number so and so —

and my nephew is a malaria patient in an army hospital.

McCormack: I am James McCormack, —

— number so and so.

My brother is in the army too. If these tests will help cure him of malaria, it will all be worth while.

Quall: Medical officers are particularly interested in this next case. Your name?

Norman; Al Norman, —

— number so and so.

Quall: Why is your case unusual, Norman?

Norman: Because I have had five relapses since I first contracted malaria; that is the highest number any patient had.

I will stop here.

I shall stop reading; I believe this gives the general impression. Is it correct that all of them are giving idealistic reasons as the motive

MR. HARDY: Prior to the question I suggest that the document be handed to Dr. Ivy if he wishes to refer to other sections of it in his answer.

DR. SERVATIUS: I shall do so immediately; however, I have one question first.

Q: Are these not all idealistic points of view as the person's motive?

A: Yes, on the basis of my discussions with people who observed these experiments at Stateville, Illinois, the idealistic motivation of this group was very high. As a matter of fact, the effect of this public service rendered by these prisoners is being followed to see whether or not that special reformative value, and up to the present time this question indicates that this public service has been of great reformative value, in that the incidents of return to criminality under parole is markedly decreased.

Q: Do you know Nathan Leopold, or do you know who he is?

A: Yes.

Q: Is it true that he was condemned to fifteen years in the penitentiary for murder?

A: For much more than that.

Q: Do you think he is the right person to give an opinion regarding the high morale status of the inmates of a penitentiary?

A: He can never expect to get out of the penitentiary, and I see no reason why he should not express himself without any duress or coercion accurately and as he feels.

Q: I shall show you this report, and please ascertain if you have any remarks to make about it.

A: No, I have none.

Q: The idealistic points of view are associated with the war — the state of war, are they not, aside from the last one?

A: No, I do not agree, because if any coercion were brought to bear upon these prisoners to serve in medical experiments, that would soon — within a week — come to the attention of the newspaper reporters and would appear on the front page of every paper — most every paper in the United States.

Q: I should like to tell you again what Jones says here. He says:

others have patriotic motives. Many have sons and brothers in the armed services.

Capt. Jones gives that as the main reason. And then other individuals are brought up who make statements in the same sense to the same effect. Is that not so?

A: I believe that is entirely reasonable, because an individual is a prisoner in a penitentiary is no reason why he should not be patriotic or love his country.

Q: Perhaps you will admit that no one would give that as his motive for helping before a German denazification court, namely, that he wanted to help the army.

A: I did not get the question. Will you please repeat it?

Q: Never mind.

Now, witness, of the experiments we have here there were none of those volunteered who were outside the penitentiary, now, why did not persons outside the penitentiary volunteer: business men or such in the malaria experiment, for example? Because we must assume that not only inmates of penitentiary have ideals?

A: As I explained yesterday, conscientious objectors were used, and also prisoners were used instead of teachers and business men because those individuals had no other duties to perform. Their time was fully available for purposes of experimentation.

Q: Is it not an evil to carry out experiments?

A: No.

Q: You don't think so.

A: It is not an evil to carry out experiments.

Q: But it isn't an evil to have to go through an experiment as an experiment subject?

A: I should say not. I have served myself as an experimental subject many times, and I do not consider it an evil.

Q: Don't you think it is very unpleasant to become infected with malaria, to have favors, and other undesirable symptoms of that sort?

A: Yes, it is unpleasant, but not an evil.

Q: Perhaps we don't understand each other. You don't want to say it is a pleasure to have malaria?

A: No, it is not a pleasure.

Q: Is it not a very unpleasant and serious disease that lasts for many years?

A: It is unpleasant, yes.

Q: If all of these persons apply for idealistic reasons, why are they offered pecuniary recompense?

A: I suppose it is to serve as a small reward for the unpleasantness of the experience.

Q: Don' t you believe that the money was the motive for army of them—a hundred dollars?

A: That is rather small: From the point of view of prisoners in the penitentiary in the United. States. A hundred dollars isn't much money.

Q: For a prisoner that would be quite a lot of money, it seems to me, for someone at liberty it is not so much.

A: No; our prisoners in the penitentiary in the United States, when they work in factories in the prisons, receive — pecuniary compensation for that work.

Q: I believe that is throughout the world.

A: That is put in a trust fund for them to use when they get out.

Q: Do you think that the money is sufficient recompense or compensation for what the experimental subject has to go through?

A: I should not consider it so, and I don't believe that any of the prisoners did. As a matter of fact, I was told that some of them would not accept the money.

Q: If one declares one's self to be a volunteer, must one not weight the advantages against the disadvantages?

A: I believe so.

Q: The disadvantage here is the risk of a serious disease, the advantage is fifty or a hundred dollars.

A: I should say the advantage is being able to serve for the good of humanity.

Q: For what reason w as the money not paid immediately—but in two payments? So far as I remember from a document yesterday, the hundred dollars was paid as follows: Fifty dollars after the first month, and the other fifty after one year. In other words, a prisoner has to do his job first. Now, why was that so?

A: I presume that that is just the common way of doing business in the United States when an agreement is involved. I presume the lawyers had something to do with that.

Q: Was the reason not this: that the prisoner would lose his enthusiasm for the experiment and would cease to cooperate? Could that have been the reason for being a little circumspect in the payment?

A: I doubt that.

Q: Do you know of case where the experimental subject did not wish to continue the experiment?

A: That has not been my experience. And according to the response that I go to that question when I put it to Dr. Irving, he said that no one expressed a desire to withdraw at any time.

Q: Professor, I have seen a document on experiments in hunger that were carried out on conscientious objectors. That appeared in a periodical. It is described how these conscientious objectors want through considerable unpleasantness and did not want to continue the experiment. They did only at great effort to continue with their promise. Is that known to you?

MR. HARDY: I suggest that Counsel refer to the document that he is talking about at this time and make it available for Dr. Ivy, or make the facts available, the particular data, so that Dr. Ivy will be fully aware of the circumstances.

THE PRESIDENT: Does counsel have a document which he can make available? Then he will use it.

DR. SERVATIUS: I have only one copy in English here. (Presented to witness). I shall have to find the passage I am referring to.

I can't seem to find it. This is a long document and somewhere there is the statement that the experimental subjects have to summon all their forces to remain in the- experiment. However, I shall drop the subject for the moment.

BY DR. SERVATIUS:

Q: Witness, is there not another inducement that persuades prisoners to volunteer for experiments? Is not the prospect of pardon or other advantages the reason for applying?

A: When these malaria experiments started, that prospect was not held out to the prisoners, hence the possibility of a reduction in sentence, in being placed on parole sooner than otherwise, was not a prospect. However, since some of these malaria experiments have been terminated a reduction of sentences in addition to that allowed for ordinary "good time" has been granted by the parole board.

For that reason Governor Green of the State of Illinois appointed a committee with me as Chairman to consider this question which you have in mind: How much reduction of sentence can be allowed in such instances so that the reduction in sentence will not be great enough to exert undue influence or constitute duress in obtaining volunteers. I have my conclusions ready and can read them to you, if you desire to hear them.

Q: Please do so. May I ask when this committee was formed?

A: The formation of the committee, according to the best of my recollection occurred in December, 1946, when the prisoners with indeterminate sentences were up for consideration for parole. This was the first time the question of reduction in sentence came up.

Q: One more question, witness. Did the formation of this committee have anything to do with the fact that this trial is going on, or with the fact that this malaria case was published in LIFE MAGAZINE and that it was explicitly stated that the experimental subjects were receiving no compensation, no pardon, reduction of sentence? Is there any connection between those things?

A: There is no connection between the action in this committee between the appointment of this committee and this trial, for this reason: that there is a division of opinion regarding the work that the parole boards do. Some believe that the parole boards are too soft; others believe that they are too hard. If a reduction in sentence were too great, parole boards would be criticized in the newspapers. Obviously the parole board wants to act on the basis of the best opinion on medical ethics that they can obtain. Accordingly, this committee was appointed.

Q: Would you please be so good as to read what you intended before?

A: There are two conclusions:

Conclusion 1: The service of prisoners as subjects in medical experiments should be rewarded in addition to the ordinary good time allowed for good conduct, industry, fidelity, and courage, but the excess time rewarded should not be so great as to exert undue influence in obtaining the consent of the prisoners. To give an excessive reward would be contrary to the ethics of medicine and would debase and jeopardize a method for doing good.

Thus the amount of reduction of sentence in prison should be determined by the forbearance required, by the experiment, and the character of the prisoner. It is believed that a 100% increase in ordinary good time during the duration of the experiments would not be excessive in these experiments requiring the maximum forbearance.

Conclusion 2: A prisoner incapable of becoming a law abiding citizen should be told in advance, if he desires to serve as a subject in a medical experiment, not to expect any reduction in sentence. A prisoner who perpetrated an atrocious crime, even though capable of becoming a law abiding citizen, should be told in advance, if he desires to serve as a subject in a medical experiment, not to expect any drastic reduction in sentence.

I might explain, when I used the expression "reduction in sentence in prison," that that implies that when the prisoner is released on parole, he is still under supervision, observation, or sentence outside of prison. He is subject to arrest and return to prison at any time; so when we say reduction of sentence in prison, we do not mean that there is an actual reduction of sentence prescribed by the court. That is the law in the State of Illinois.

Q: Witness, if the experimental subjects are prisoners, are they told about this policy ahead of time?

A: They will obviously have to be told of this policy from now on, since the matter has come up for the first time.

Q: Yesterday a prosecution document was shown to you. That was Exhibit 517, Department of Justice, Bureau of Prisons, a document from Texas.

This was in no document book but was put in only yesterday. I shall have this shown to you immediately. In it it states the following: This is a form from the Department of Justice, Bureau of Prisons, a statement of voluntary consent and it says here the following:

I agree to cooperate to the fullest extent with the physicians conducting the study during an over-all observation period of approximately 18 months. I understand that at the conclusion of the observation period, I am to be furnished with an appropriate certificate of Merit and a statement of my voluntary cooperation in the study and the fact that I have thus rendered voluntarily an outstanding service to humanity will be placed in my official record.

Is that not a rather extensive promise which might induce a prisoner to apply without having a purely idealistic motive?

A: A Certificate of Merit is an attractive little certificate that the prisoner could have framed and he could hang on the wall of his prison cell. After he was released, he could take it home and show it to his friends, and I think it might serve as an incentive to lead the previous wrong-door not to go into the way's of wrong doing again.

Q: Do you not think that it has a very practical usefulness? Do you not think that it could lead the police to treat one a little more leniently?

A: I doubt it, although I can't testify regarding what the police might do.

Q: Don't you think that it would be of some aid when looking for a job after his release?

A: When a prisoner is released on parole, before he is released, a job is found for him.

Q: You try to get such a job. Do you always find one?

A: He would not be released unless a job had been found for him. That is part of the penal system.

Q: But, if this is a prisoner who is in prison for a specific and definite sentence and who after having served his term is released, does not this certificate of merit stand him in very good stead in his search for a job?

A: I do not know that such ever occurred because we have agencies whose function it is to find jobs for prisoners released from the penitentiary so that they will not be tempted to go back into the ways of crime because the major purpose of the penal system in the United States today is reformative rather than punitive.

Q: The prisoner takes this certificate of merit with him home in order to show that he has improved and that he has voluntarily done atonement. So this does play a role, doesn't it?

A: That may be one way of looking at it.

Q: Was there not such a case in the first document that I showed to you, the radio report where the letter writer says, "I am condemned for life and I want to help because the Army wants me to." Was this not, also, the thought of atonement?

A: I would say it was the thought of being able to do a good deed for humanity whereas in the past the individual prisoner had not performed good deeds. It may in that way be considered an atonement or expatiation or expiation.

Q: was that not one of the main thoughts that the the public has, namely it is more or less demanded that a prisoner make himself available for experiments? Is not public opinion the place where you find this view represented?

A: No, not at all.

Q: I want to put two articles to you. You know the newspaper, The Stars and Stripes, the Army newspaper?

A: I know such a paper exists, yes.

Q: And do you know that it is the newspaper with the largest circulation among soldiers here in the continent?

A: I don't know that but I should presume so.

Q: I will put a document to you. For identification purposes it will get Exhibit number KB 113.

MR. HARDY: Your Honors, I must object to the admission of this document in evidence. This is merely an opinion of a Staff Sergeant in the United States Army in what might be the B bag section. It looks to me like a matter of that sort. I don't think it would have any value here. I might pass it up to the Tribunal for your perusal.

THE PRESIDENT: What is your theory, counsel, in considering this paper marked 301 and 113?

DR. SERVATIUS: I got this excerpt from the newspaper which is published here in Germany. I received it, it was used in another trial and I am putting it in because it seems to me its contents are material. The question is whether experiments can be carried out on prisoners from the point of view of their doing atonement. I am of the opinion that experiments carried out in Germany could be ordered by the State because urgently needed by the State and that they could be carried out as atonement in prisoner's sentences. And, in order to prove a general view and not confined to the Third Reich I am putting in this newspaper article and I also want to put in an article from an English newspaper, "The People", to the same effect. However, the English writer Llewellyn is expressing the opinion of other people without criticizing it and also says that the element of atonement plays a part.

JUDGE SEBRING: Dr. Servatius, do you maintain that the name that is supposed to be signed to this article is the name of someone who is supposed to be an authority in this subject or is supposed to represent some considerable segment of world opinion?

DR. SERVATIUS: I cannot make that statement because I do not know the man. However, this is a periodical with a great circulation and this article went through the censorship.

This then is an article regarded as pertinent in authoritative circles. Of course, this thing here aroused great excitement in SS circles and is not an article just sent in.

JUDGE SEBRING: Is it your view that you are of the opinion that this represents some considerable segment of American thought.

DR. SERVATIUS: It was so striking that it could go through the censorship which is here for the soldiers and could appear in the country where reading of such an article would cause great excitement. The important thing is not who wrote it but the main thing is it passed the censors.

JUDGE SEBRING: What is the provocative fact sought to be elicited in presenting this thing here to the witness?

DR. SERVATIUS: I wish to put it to the witness in order to hear from him whether this also is an expression of the idea of atonement of which the witness has already spoken. And I should like to add the thought is expressed in this newspaper which is well known to us defense counsel from the main trial — IMT. Again and again we received letters in which such things were expressed, from Germany and America. So that I say the motive of atonement is not something I pulled out of my hat but an idea readily circulated and which has wide circulation. I do not have the actual newspaper here but I have a certified copy. I am not offering it as a document I just want to read it.

THE PRESIDENT: The Tribunal will assume that this is a correct copy of what purports to be a letter printed in the Stars and Stripes. The matter is entirely without probative value. The opinion of the witness on the matter would not aid the Tribunal on the matter which is a matter of some sensational letter that was written. The Tribunal does not desire to waste any time at all on the matter. Objection is sustained.

Q: Mr. President I ask permission to put to the writer a small newspaper notice from the newspaper "The People" of 3 March 1946. This is an English Newspaper. Regarding the defendants before the IMT the following was stated:

The opinion of some people is that they should be condemned very soon. Then it says:

Others believe that they should be made to expiate their crimes by helping to cure cancer, leprosy and tuberculosis as bodies for experiments.

Is the thought of atonement contained therein?

A: Yes, but it is expressed in a hysterical manner.

Q: Yes, I agree with you.

Witness, do you believe that if a person does not volunteer for an experiment the State can order such atonement?

A: No.

Q: Do you not believe that you can expect something of a prisoner that goes beyond his actual sentence if at the same time people outside a prison are subject to such burdens?

A: No. Those ideas were given up many years ago in the science and study of penology. The primary objective of penology today is reformative not punitive, not expiative.

Q: Witness, is that the recognized theory of penology throughout the whole world today?

A: It may not be the recognized theory throughout the whole world today, but it is the prevailing theory in the United States. There is one other aspect that is quite large and essential, and that is the protective aspect of imprisonment, to protect society from a habitual criminal.

Q: Witness, if a soldier at the front is exposed to an epidemic and can be almost certain that he will catch typhus and deserts and hides behind the protecting walls of a prison, would you not consider it justifiable if he is persuaded to volunteer for an experiment that concerns itself with typhus?

A: Will you read the question again?

Q: If a soldier deserts from the front where typhus is raging for fear that he too will contract typhus and prefers to be imprisoned in order thus to save himself, do you think it is right for him to be persuaded while he is serving his sentence to subject himself to a typhus experiment?

A: As a volunteer? Yes.

Q: I see. And would you not take a step further, if this prisoner says, "No, I refuse, because if I do this there wouldn't have been any point in my deserting; I deserted in order to save myself. My buddies may die but I just would prefer not to."

A: The answer to that question is no.

Q: Don't you admit that one can hold a different view in this matter?

A: Yes, but I don't believe it could be justified.

Q: Witness, take the following case, You are in a city in which plague is raging. You, as a doctor, have a drug that you could use to combat the plague. However, you must test it on somebody. The commander, or let's say the mayor of the city, comes to you and says, "Here is a criminal condemned to death. Save us by carrying out the experiment on this man." Would you refuse to do so, or would you do it?

A: I would refuse to do so, because I do not believe that duress of that sort warrants the breaking of ethical and moral principles. That is why the Hague Convention and Geneva Convention were formulated, to make war, a barbaric enterprise, a little more humane.

Q: Do you believe that the population of a city would have any understanding for your action?

A: They have no understanding for the importance of the maintenance of the principles of medical ethics which apply over a long period of years, rather than a short period of years.

Physicians and medical scientists should do nothing with the idea of temporarily doing good which when carried out repeatedly over a period of time would debase and jeopardize a method for doing good. If a medical scientist breaks the code of medical ethics and will say, "Kill the person," in order to do what he thinks may be good, in the course of time that will grow and will cause a loss of faith of the public in the medical profession, and hence destroy the capacity of the medical profession to do its good for society. The reason that we must be very careful in the use of human beings as subjects in medical experiments is not to debase and jeopardize this method for doing great good by causing the public to react against it.

Q: Witness, do you not believe that your ideal attitude here is more or less a single person standing against the body of public opinion?

A: No, I do not. That is why I read the principles of medical ethics yesterday, and that is why the American Medical Association has agreed essentially with those principles. That is why the principles, the ethical principles for the use of human being's in medical experiments have been quite uniform throughout the world in the past.

Q: Then you do not believe that the urgency, the necessity of this city would make a revision of this attitude necessary?

A: No, not if they were in danger of killing people in the course of testing out the new drug or remedy. There is no justification in killing five people in order to save the lives of five hundred.

Q: Then you are of the opinion that the life of the one prisoner must be preserved even if the whole city perishes?

A: In order to maintain intact the method of doing good, yes.

Q: From the point of view of the politician, do you consider it good if he allows the city to perish in the interests of preserving this principle and preserving the life of the one prisoner?

A: The politician, unless he knows medicine and medical ethics, has no reason to make a decision on that point.

Q: But as a politician he must make a decision about what is to happen. Shall he coerce the doctor to carry out the experiment, or shall he protect the doctor from the rage of the multitude?

A: You can't answer that question. I should say this, that there is no state or no politician under the sun that could force me to perform a medical experiment which I thought was morally unjustified.

Q: You then, despite the order, would not carry out the order, and would prefer to be executed as a martyr?

A: That is correct, and I know there are thousands of people in the United States who would have to do likewise too.

Q: And do you not also believe that in thousands of cities the population would kill the doctor who found himself in that position?

A: I do not believe because they would not know. How would they know whether the doctor had a drug that would or would not relieve? The doctor would not know himself, because he would have to experiment first.

Q: Witness, I put a hypothetical case to you. If we are to turn to reality other questions would arise. I simply want to hear now your general attitude to this problem. You are then of the opinion that a doctor should not carry out the order. Are you also of the opinion that the politician should not give such an order?

A: Yes, I believe he should not give such an order.

Q: Is this not a purely political decision which must be left at the discretion of the political leader?

A: Not necessarily. He should seek the best advice that he can obtain.

Q: If he is informed that this one experiment on this one prisoner would save the whole city, he may give the order despite the fact that the doctor does not wish to carry it out, is that what you think?

A: He then could give the order, but if the doctor still believed that it was contrary to his moral responsibilities then the doctor should not carry out the order.

Q: That is another question, whether or not he carries it out, but in such cases you consider it is permissible to give that order, is that what I understood you to say?

A: After he has obtained the best advice on the subject which he can obtain.

Q: Then he can give the order, yes or no?

A: Yes.

DR. SERVATIUS: Mr. President, I am turning now to another theme. Perhaps this would be a good time to recess.

THE PRESIDENT: Your estimate of the time you would take to cross examine this witness was forty-five minutes, which you have now exceeded. How much longer will your cross-examination continue?

DR. SERVATIUS: Mr. President, my questions were short, but the answers were long. I have a number of questions, not too many. It does not depend on me, but I can assume that I shall be done in half an hour.

MR. HARDY: Your Honor, I might state, if you would try to determine the length of time which it will be necessary to keep Dr. Ivy on the witness stand, that the Prosecution's redirect examination will be very, very brief, if any at all.

THE PRESIDENT: I understand that Dr. Nelte, on behalf of the Defendant Handloser, desires to ask some questions which he estimated at fifteen minutes. Dr. Flemming on behalf of the defendant Mrugowsky will cross-examine the witness, the doctor stated, to the extent of about fifteen minutes. Dr. Steinbauer, of course, on behalf of the Defendant Beiglboeck will have cross-examination of the witness which the doctor estimated at an hour, is that correct?

DR. STEINBAUER: An hour to an hour and a half. It depends upon the answers.

THE PRESIDENT: It appear that this counsel —

DR. FRITZ (For Defendant Rose): Mr. President, I too wish to put questions to the expert witness. Roughly an hour is what I shall need.

MR. HARDY: I thought that would be the import of the questions put to the witness by the defense counsel for Rose. I thought he would take up general questions for all counsel.

DR. TIPP (For Defendant Becker-Freysang): I shall wish to ask a few questions for Becker-Freysang, to be sure not too many. This, however, will take half an hour.

THE PRESIDENT: Unless the Tribunal is to sit this afternoon, counsel must be prepared to confine themselves to the time which they have estimated for examination on Monday. Counsel understands that if we do not hold an afternoon session today that they must be limited on their cross-examination Monday to the time which they have estimated. Do defense counsel understand that? There will be time Monday to complete the cross-examination with the understanding that defense counsel will limit themselves to the time which they have estimated. They will be held to that limit.

DR. KAUFFMANN (For Defendant Rudolf Brandt): Mr. President, I do not know whether you have included the time that I need. I shall need roughly ten minutes for Rudolf Brandt.

THE PRESIDENT: I did not know that Dr. Kauffmann was going to participate in the examination.

It will be understood the Tribunal will not hold a session this afternoon. It will be understood the defense counsel will be limited to available time on Monday in which all defense counsel must complete their cross-examination of the witness half an hour before closing time Monday afternoon.

The Tribunal will now be in recess until nine-thirty o'clock Monday morning.

THE MARSHAL: The Tribunal will be in recess until nine-thirty o'clock Monday morning.

(The Tribunal adjourned until 16 June 1947, at 0930 hours.)