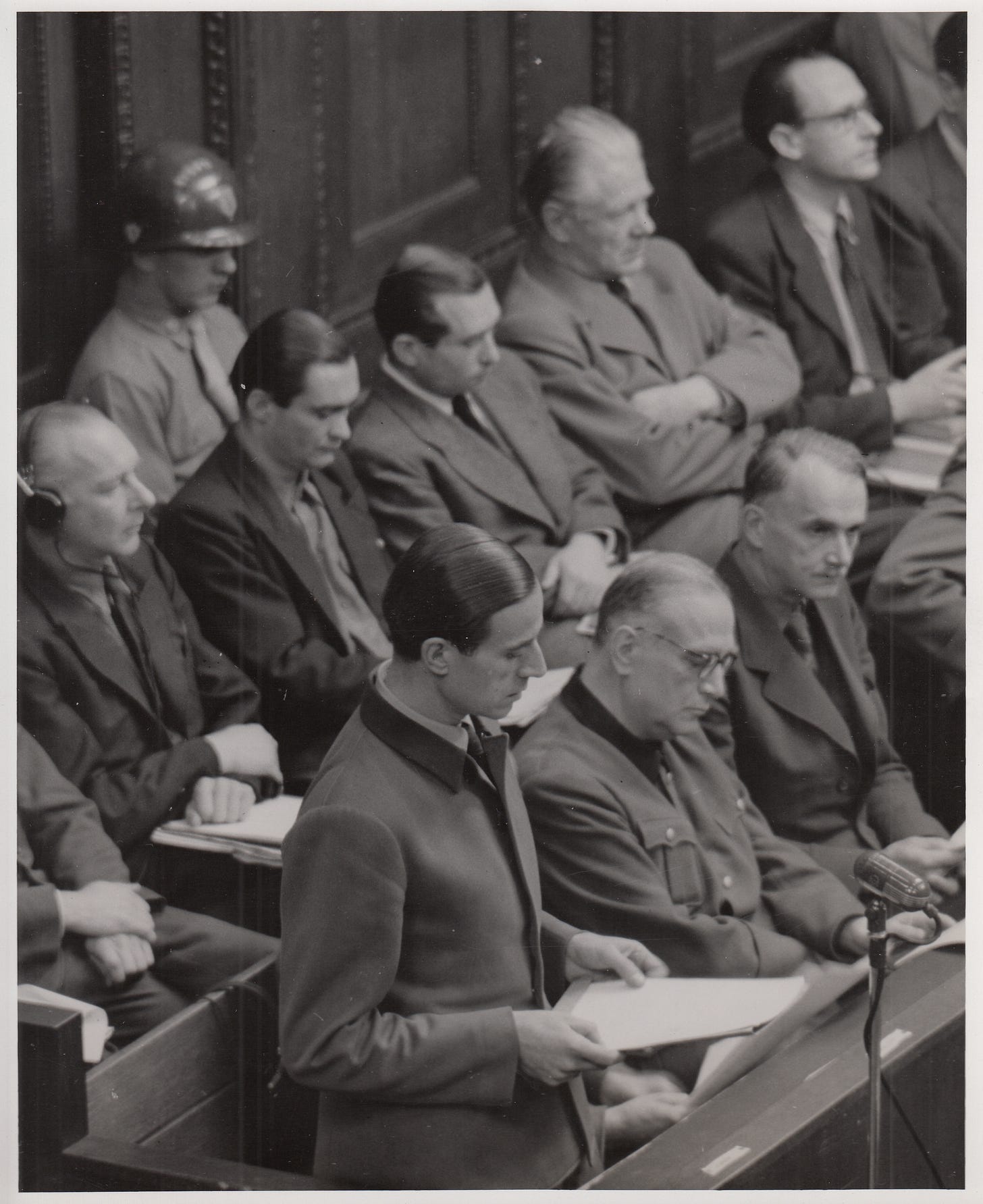

1947-07-19, #2: Doctors' Trial (Karl Brandt's personal statement)

THE PRESIDENT: Karl Brandt.

DEFENDANT KARL BRANDT: There is a word which seems so simple, and that is the word order, and yet how atrocious are its implications, how immeasurable are the conflicts which hide behind the word. Both affected, me, to obey and to give orders, and both are responsibility. I am a doctor and before my conscience there is this responsibility as the responsibility towards men and towards life. Quite soberly, the prosecution charged crimes and murder and they raised the question of my guilt. It would be without significance if friends and patients were to shield me and to speak well of me, saying I had helped and I had healed. There would be many examples for my actions during danger and my readiness to help.

But all that is now different. For my sake I shall not evade these charges. But there is the attempt of human justification which is my duty towards all who believe in mo, who trust in me and who relied upon me as a man, as a doctor and as a superior.

I have never regarded the human experiments in whatever shape I might have meant it as a matter of course, not even when it was without danger. But I affirm it for the sake of reason that it is a necessity. I know that from these contradictions will arise. The things that disturb the conscience or a medical man, and I know the inner feeling that urges one when an order or when obedience decide the morale of any type.

It is immaterial for the experiment when this is done with or against the will of the person concerned. For the individual the event remains contradictory, just as contradictory as my actions as a doctor seem to be if you decide to isolate it. The sense is much deeper than that. Can I, as an individual, remove myself from the community? Can I be outside and without it? Could I, as a part of this community, evade it by saying I want to thrive in this community, but I don't want to bring any sacrifices for it, not bodily and not with my soul. I want to keep my conscience clear. Let them try how they can got along. And yet we, that community, are somehow identical.

Thus I must suffer of these controversies, bear the consequences, even if they remain incomprehensible. I must bear them as the fate of my life which allocates to me its tasks. The sense is the motive, devoted to the community. If for their sake I am guilty, then for their sake I will justify myself.

There was war. In war one's actions are all alike. Sacrifices of war affect us all and I stand by them. But are those sacrifices my crime? Did I kick the requirements of humanity and despise them? Did I step across human beings and their lives as if they were nothing? Yes, they will point at me and cry "Euthanasia" — and wrongly; useless, incapable, without value. But what did happen? Did not Pastor Bodelschwingh in the middle of his work at Bethel last year say that I was an Idealist and not a criminal. How could he do such a thing? Here I am, subject of the most frightful charges. What if I had not only been a doctor but a man too without a heart and without a conscience. Would you believe that it was a pleasure to me when I received the order to start Euthanasia For 15 years I had labored at the sick-bed and every patient was to me like a brother, every sick child I worried about as if it had been my own.

And then that hard fate hit me. Is that guilt?

Was it not my first thought to limit the scope of Euthanasia? Did I not, the moment I was included, try to find a limit and find a cure for the incurable? Were not the professors of the Universities there? Who could there be who was more qualified? But I do not want to speak of those questions and of their executions. I defend myself against the charge of inhuman conduct and base philosophy. In the face of those charges I fight for my right to humane treatment. I know how complicated this problem is. With the deepest devotion I have tortured myself again and again, but no philosophy and no other wisdom helped here.

There was the decree and on it there was my name. I do not say that I could have feigned sickness. I do not live this life of mine in order to evade fate if I meet it. And thus I affirmed Euthanasia. I realize the problem is as old as man, but it is not a crime against men nor against humanity. Here I cannot believe like a clergyman or think as a jurist. I am a doctor and I see the law of nature as being the law of reason. From that grew in my heart the love of men and it stands before my conscience. When I talked to Pastor Bodelschwingh, the only serious warning voice I ever met personally, it seemed at first as if our thoughts were far apart, but the longer we talked and the more we came into the open, the closer and the greater became our mutual understanding. At that time we weren't concerned with words. It was a struggle and a search far beyond the human scope and sphere.

When the old Pastor Bodelschwingh after many hours left me and we shook hands, he said as his last word, "that was the hardest struggle of my life." To him as well as to me that struggle remained, and it remained a problem too.

If I were to say to-day that I wished that this problem had never hit me in its tremendous dramatic force, then this could be nothing but superficiality in order to make it more comfortable for myself. But I live in my time and I experience that it is full of controversies everywhere. Somewhere we all must make a stand.

I am deeply conscious before myself that when I said "Yes" to Euthanasia I did that in my deepest conviction, just as it is my conviction today, that it was right. Death can mean relief. Death is life — just as much as birth. Never was it meant to be murder. I bear this burden but it is not the burden of crime. I bear this burden of mine, though, with a heavy heart as my responsibility. Before it, I survive and pass, and before my conscience, as a man and as a doctor.