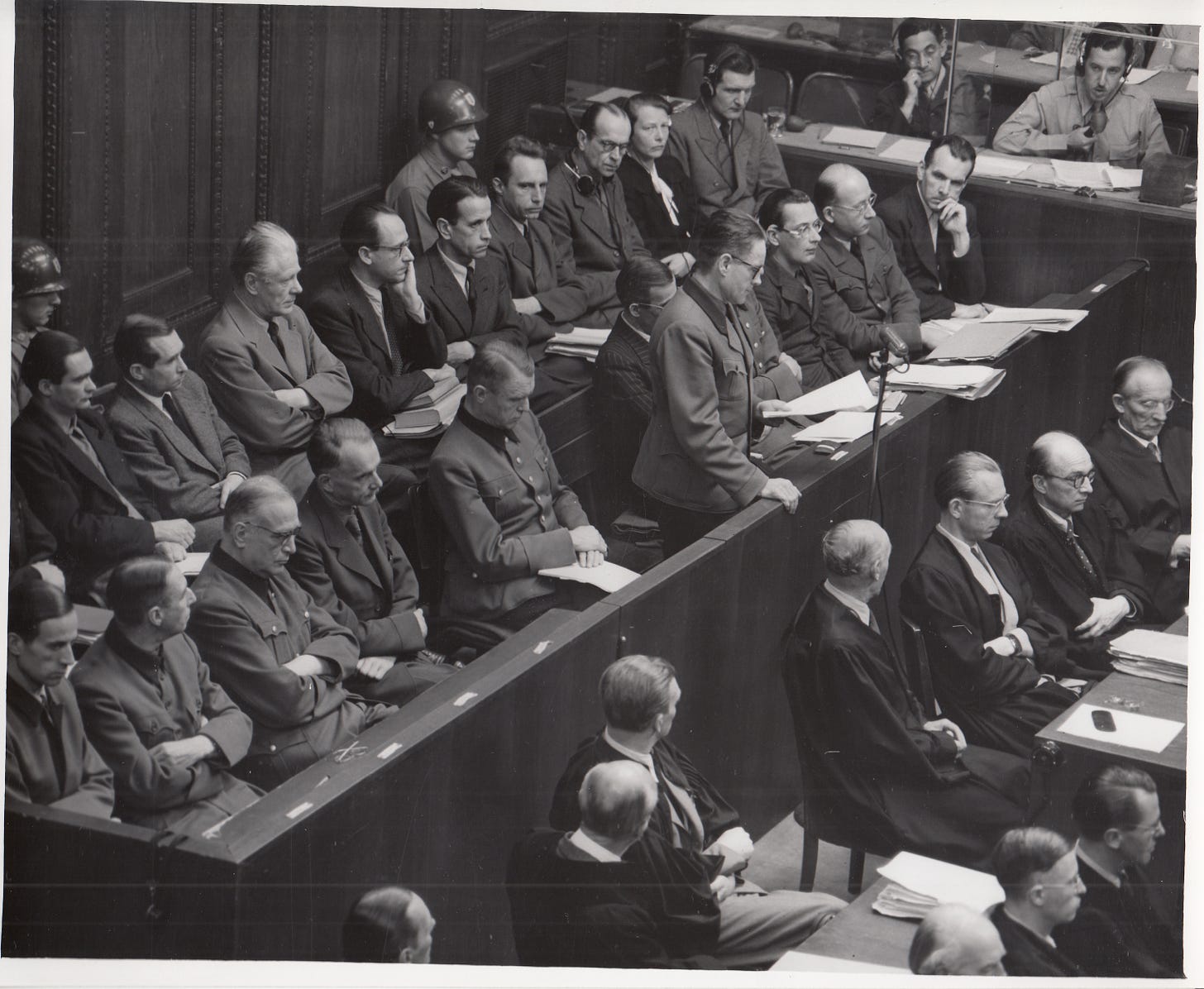

1947-07-19, #7: Doctors' Trial (Karl Gebhardt's personal statement)

THE PRESIDENT: The defendant Gebhardt.

DEFENDANT GEBHARDT: I wish to thank the High Tribunal for having granted me an opportunity, in the witness box, to describe my personal position in 1942 in that much detail.

The historical situation at that time placed me in a totalitarian state which, in turn, placed itself between the individual and the universe. The virtues in the service of the state were virtues as such. Beyond that, I did not know whether, in the world neurosis of this total war, there was a country at all where the spirit was not used as a tool for war. Everywhere, in some way, values and solutions were put in the service of the war. And here again, in the spiritual field, the first step is the decisive one.

I may be permitted to recall that in the war of nerves, propaganda with and for medical preparations caused the first step, the order to examine the problem of sulfanilamides.

In my final statement today I want to describe my entire attitude as a whole. In doing so, may I utilize the most important of the four American freedoms, that is to say, the freedom of speech, until the very end, in a manner wherein I will refrain from any denunciation or from incriminating others. Without exaggerating the importance of my own person.

However, any physician can only be measured according to his idea of medical science. Basically, I was neither a cold technical specialist nor a pure scientist. I believe that I have always tried, for example, when carrying out surgical experiments, to see every disease as a purely human condition of suffering. However, I did not see my task as something to serve my own advantage, nor in cheap gestures of theoretical pit, but, in my personal active service, to support the wavering existence of the suffering patient. That is how I saw my task. My goal as a physician was not so much purely technical therapy for the individual patient, but therapeutical care for the particularly underprivileged group of the poor, the children, the cripples, the neurotics.

I am mainly interested in succeeding in being believed that it was not for moral baseness nor for selfish arrogance of the scientist that I came into contact with experiments on human beings. On the contrary, during the entire period in question I had animal experiments carried out in my field of research.

However, since I was the competent, responsible surgical expert, I was informed about the imminent experiments on human beings in my surgical fields ordered by the National authorities. After the order was given, it was no longer a question of stopping these experiments, but the problem was the method of their being carried out.

As an expert, my conflicts consisted of the following: For one, the experiments that had been ordered had to be of practical scientific value, and with the aim that a preventive should be found to protect thousands of injured and sick. On the other hand, I considered humane safety measures for the experimental subjects most important. The focal point for me, indeed, was never the purpose and the goal of the experiments, but the manner in which they were carried out. To do that in a humane way, I did not remain aloof in the special surgical field; I did not restrict myself to theoretical instruction, but I took part with my clinic and with all its safety measures.

I hope that this bears out the fact that in carrying out experiments I tried with the best of intentions to act primarily in the interest of the experimental subjects. We did not take advantage of the opportunity which was given us by Himmler without limitation. That is to say, surgical experiments were not followed by others. I believe that as far as that was possible at that period that I have fulfilled my duty as an expert purely because these experiments did not increase in the surgical field in spite of the crescendo of policy at that time. My desire was to help and not to give a bad example. In choosing this way of justification, of course, I have made a decision for myself. I hope that up to now I always stood up under criticism from the very beginning in foreign countries without any secrecy but also without the feeling of guilt for my activity as an expert.

That activity of experiments as a military physician, not on my initiative, brought me in contact with a concentration camps I can understand. How heavy that deadly shadow must weight upon anyone who was ever active there. The ghostly phenomenon of that sphere, which a.t that time was unknown to me as well, can be recognized now in retrospect in full. We realize the terror in the secretly negative ideology of extermination combined there with the negative selection of the guards. Only from the files of the International Trial could we see that in the end of the 35,000 guard troops there were only 6,000 SS men unfit for combat. On the rest were scums, draftees, foreigners, etc., who to the greatest injustice and the greatest shame were given the same uniform that we wore in combat.

As chief of a well know clinic and supported by its known measures of safety devices, in the interest of the experimental subjects I got in touch, within the framework of my duty as an expert, with concentration camp doctors. As far as it was at all possible I tried to exclude that atmosphere in my field. But, I believe it can be realized that my counter-actions vent beyond purely clinical safety measures in the interest of the experimental subjects because of the several thousand foreign inmates of this concentration camp, among whom as we were told here there were at least seven hundred Polish women (only two hundred), but of these two hundred sixty of my experimental subjects, as was proved, at the end of the war were turned over to the Red Cross.

As much as I might try to clarify my actions as a doctor and to explain my good intentions and position there, here in the same manner my final thought should be devoted to self-criticism and to concentrate on my moral obligation.

In a parody on a statement by Heinrich Heine we may see today "It is fate in itself to have been an SS man regardless in what position". Though I believe and hope that I did my duty in this confusion which has been recognized later as being a most dreadful one — the confusion between the decent Waffen-SS and the executive organization, that I have done my duty as an officer, a doctor, and a human being — I still feel highly responsible and I have my own restitution from this confusion — my possibilities to do that of course were limited.

Without looking for sensation I offered to undergo a self-experiment as proof, and that without any surgical safety measures, as soon as the first opportunity existed. My responsibility to all those who were my subordinates I have emphasized. I further have a responsibility, which I state not only now in the dim light of my own defense but already stated in May 1945 on that day when Himmler released us from our oath and from our orders and he himself left his post without any ethical reserve or ideological foundation. It. was my endeavor to prevent any illegal continuation of the ideas of the SS, to take the burden off the shoulders of our faithful youth by burning over the SS Generals.

Today as one individual I can only repeat to my colleagues that readiness. Here, in spite of my serious endeavor, the charges seem to give a different impression. May the consequences effect me in such a way that I may ease the problem to the younger ones who, believing in me, also joined the SS as surgeons. I believe that this pile of rubble of Germany can not afford to let these good young doctors perish in camps or in inactivity. Likewise I understand I have measures which should make the work easier for the old German universities and their admired teachers.

If you permit me a last sentence without referring to my own person, in order to summarize what I have found out in order to avoid possible mistakes, I would like to say, that from basic social conditions the only pathological escape at that time, as well as today, would be here as well as everywhere, to confuse and combine the spiritual with the economic and political concepts. It is a disastrous error to confuse the organized unanimity of voices with harmony. Destructive criticism educates people only to be capable of cooperation. The private as well as the public conscience can not be subjugated to any official virtue nor to any temporal moral principles. That can only find its place within a God-given order. Thus, in the sense of a. constructive pessimism, as I have set forth before, this war, in this sense we alone find consideration for the reality, full of suffering, of this social catastrophe.

My last statement of gratitude is to go to Dr. Seidl who in this time which lacks of civil courage, has been our assistant as well as for my colleagues as well as for myself.