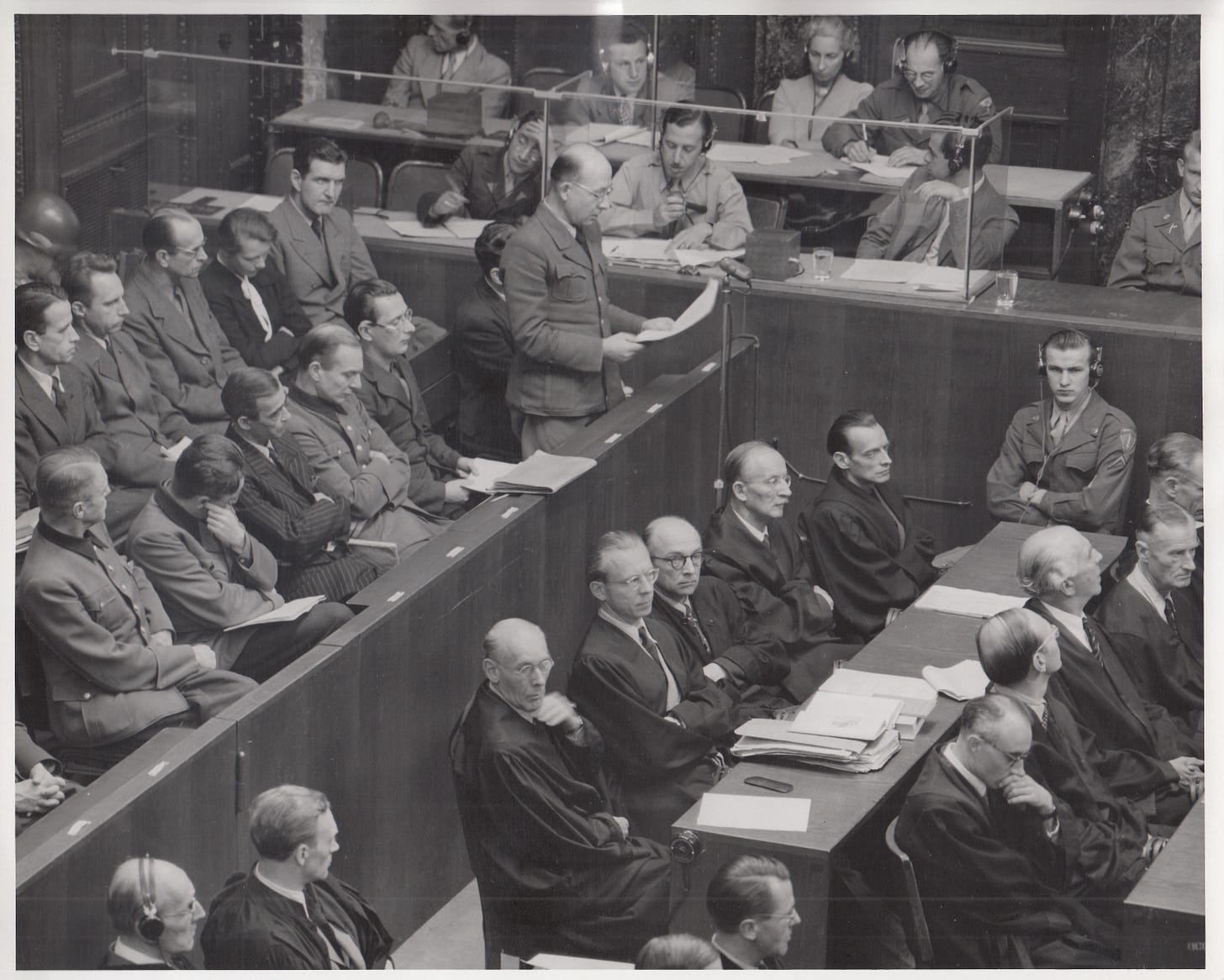

1947-07-19, #11: Doctors' Trial (Helmut Poppendick's personal statement)

THE PRESIDENT: The defendant Poppendick.

DEFENDANT POPPENDICK: I joined the SS at a time not to commit crimes, but the reason was that a number of individuals whom I knew to be idealists among my friends were members of the SS. Their membership caused me to join. That I thereby became a member of a criminal organization was unimaginable for me at that time, just as it is incomprehensible for me today. My activity in the Rasse und Siedlungs Amt (race and resettlement office) was devoted to the problem of the family, an activity which in view of the destructive tendencies during the period of the first World War seemed important to me.

If my expectations as a physician were disappointed in more than one point, at least I considered myself justified to hope that in the end this activity would have positive results. The intentions were always toward a constructive policy for the good of the family. Never did I have anything to do with negative population policies, not even outside of policies of a legal nature, as the sterilization program of the State.

The assertion of the prosecution that positive and negative population policies belong in the same chapter, just as the two different sides and possibilities of one program, is erroneous. Then there were purely organizational reasons which brought about my direct subordination under the office of that man whose name today has such an inhuman sound — I mean Grawitz.

The impression which the prosecution ha.s rendered of my activity and position in Grawitz' office is not in accordance with the facts, in spite of some features which seem to support the assertion made by the prosecution.

As for medical experiments on inmates — experiments on human beings were nothing surprising to me, nor anything new. I knew that experiments were carried on in clinics. I knew that the modern achievements of medical science had not been brought about without sacrifices.

However, I do not recall that the fact of voluntary experimental subjects had to be an absolute requirement, as it seems to be considered as a matter of fact, according to the discussions in this trial. I knew furthermore, that some scientific problems can only be solved by experiments in series with conditions remaining constant, and that therefore soldiers and particularly soldiers in camps are used for experiments in all countries.

Under these circumstances it did not appear surprising to me that during the war scientists also Carried out experiments in series in concentration camps. I did not have the least Cause to assume that these scientists in the camps would go beyond the scope of that which otherwise everywhere in the world of science was customary.

What I knew about medical experiments in the SS was, in my opinion not at all connected with criminal matters, not any more than those experiments about which I knew from my clinical experience before 1933.

In March of this year a young doctor, Dr. Mitchelich, in a very one-sided way, published a book containing the indictment, "The Dictates of Contempt for Human Life". The problem found in this book, is the basis for an opinion, of course, and the basis for a verdict seemed to be quite clearly offered.

During the very last days, however, the Chief of Dr. Mitchelich, a well-known Professor from Heidelberg, Weizaeker, published a study on the principle questions belonging to the subject under the title "Euthanasia and Experiments on Human Beings", which he had submitted to the defendants. But here now we find an entirely different language. The problem itself becomes obvious. If one reads this booklet then the extent of that entire problem can be seen, and its complicated features.

The oath of Hippocrates, according to Weizaecker, has nothing to do with the problem. Weizaecker applies entirely different ethical norms. Rightly the spirit of medicine of Germany, or of Germany under Hitler. It is found, therefore, that experts who consider themselves competent even today, are right in the middle of their endeavor to clarify the problems at the basis, that being the first requirement for their solution.

Before this trial all of these matters were no problems for me. I did not know of any transgressions. Moreover, I was always convinced that anything which came to my knowledge about experiments on human beings in clinics of the state before 1933, and within the scope of the SS in later years, were conscientious efforts of serious scientists to the good of mankind.

The ethical foundation of these matters also seemed to be there until this trial. Therefore, after sincere examination of my conscience, I cannot find any feeling of guilt and expect with a clear conscience, the verdict of the Tribunal.