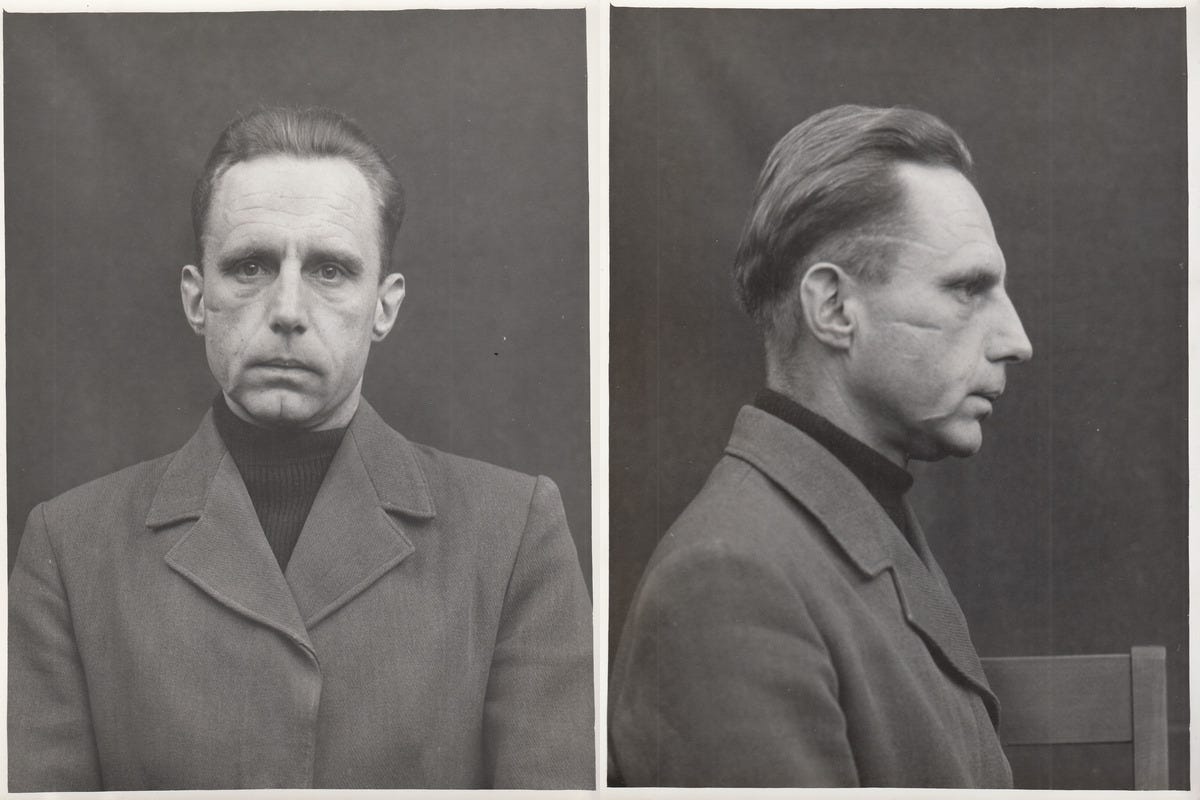

1947-08-19, #22: Doctors' Trial Verdict — Dr. Wilhelm Beiglboeck

Judgment: Wilhelm Beiglboeck — GUILTY ON ALL COUNTS

THE PRESIDENT: Judge Sebring will continue with the reading of the judgment.

THE CASE OF THE DEFENDANT WILHELM BEIGLBOECK

JUDGE SEBRING: The defendant Beiglboeck is charged with personal responsibility for, and participation in, seawater experiments.

The defendant Beiglboeck, an Austrian citizen, was a Captain in the Medical Department of the German Air Force from May 1941 until the end of the war. In June, 1944, while stationed at the hospital for Paratroopers at Tarvie, Italy, he receive orders from his military and medical superior, defendant Becker-Freyseng, to carry out seawater experiments at Dachau.

The seawater experiments have been described in detail in that portions of the Judgment dealing with defendants Schroeder and Becker-Freyseng.

The defendant Beiglboeck testified that he reported to Berlin at the end of June 1944, where Becker-Freyseng told him the nature and purpose of the experiments. Upon that trip he also reported to and talked with the defendant Schroeder. From these conversations he learned that the prime purpose of the experiments was to test the process developed by Berka for making seawater potable and also to ascertain whether it would be better for a shipwrecked person in distress at sea to go completely without seawater or to drink small quantities thereof.

It appears from the record that the persons used in the experiments were 40 Gypsies of various nationalities who had been formerly at Auschwitz but who had been brought to Dachau under the pretext that they were to be assigned to various work details. These persons had been imprisoned in the concentration camps on the basis that they were "Associal persons." Nothing was said to them about being used as human subjects in medial experiments. When they reached Dachau some of them were told that they were being assigned to the seawater experiment detail.

Beiglboeck testified that before beginning the experiments he called the subjects together and told them the purpose of the experiments and asked them if they wanted to participate. He did not tell them the duration of the experiments, or that they could withdraw if ever they reached the physical or mental state that continuation of the experiment should seem to them to be impossible. The evidence is that none of the experimental subjects felt that they dared refuse becoming experimental subjects for fear of unpleasant consequences if they voiced any objections.

The defendant testified that pursuant to the order that had been given him, it was necessary that the subjects to thirst for a continuous period; and that the question of when, if ever, they should be relieved during the course of the experiment was a matter which he reserved for his own decision.

During the course of the experiments the subjects were locked in a room. As to this phase of the program the defendant testified that "They should have been locked in a lot better than they were because then they would have had no opportunity at all to get fresh water on the side."

At the trial the defendant produced clinical charts which he said were made during the course of the experiments and which, according to the defendant, showed that the subjects did not suffer injury.

On cross-examination the defendant admitted that some of the charts had been altered by him since he reached Nurnberg in order to present a more favorable picture of the experiments.

We do not think it necessary to discuss in detail what is shown by the charts either before or after the fraudulent alterations. We think it only necessary to say that a man who intends to rely on written evidence at a trial does not fraudulently alter such evidence from any honest or worthy motive.

The defendant claims that he was at all times extremely reluctant to perform the experiments with which he is charged, and did so only out of his sense ob obedience as a soldier to superior authority.

Under Control Council Law No. 10 such fact does not constitute, but will be considered, if at all, only in mitigation of sentence.

In our view the experimental subjects were treated brutally. Many of them endured much pain and suffering, although from the evidence we cannot find that any deaths occurred among the experimental subjects.

It is apparent from the evidence that the experiments were essentially criminal in their nature, and that non-German nationals were used without their consent as experimental subjects. To the extent that the crimes committed by defendant Beiglboeck were not war crimes they were crimes against humanity.

CONCLUSION

Military Tribunal I finds and adjudges the defendant Wilhelm Beiglboeck guilty under Counts Two and Three of the Indictments.

We will now turn to the case of Pokorny.