1947-02-25, #2: Doctors' Trial (mid-morning)

THE MARSHAL: The Tribunal is again in session.

DR. MARX: Mr. President, I took advantage of the recess to inquire whether my document book is translated yet, but unfortunately I learned that the document book is not ready yet, although I ordered it at least a week ago to be translated. However, I am in a position to begin the case for the defendant, Professor Doctor Schroeder.

THE PRESIDENT: Has counsel any witnesses he could produce and put on the stand at this time?

DR. MARX: I would call the defendant, Professor Dr. Schroeder to the stand as a witness now.

THE PRESIDENT: The witness Schroeder will take the witness stand — the defendant Schroeder will take the witness stand.

MR. HARDY: May it please your Honors, may I interrupt for a moment? I have not as yet received from defense counsel a list of the witnesses to be called on behalf of the defendant Schroeder, and I would like to call that to the attention of the defense counsel so that we will be properly notified.

THE PRESIDENT: Witness, you will hold up your right hand and be sworn, repeating after me:

I swear by God, the Almighty and Omniscient, that I will speak the pure truth, and will withhold and add nothing.

(The witness repeatedly the oath)

You may be seated.

Counsel will note the statement by counsel for the Prosecution that no lists of witnesses for the defendant Schroeder have been presented and counsel will prepare the list of witnesses as soon as possible and serve it on the Prosecution.

I would ask the Secretary General if he has any information as to when the document book on behalf of the defendant Schroeder will be prepared.

The Tribunal is informed by the office of the Secretary General that document book is expected this morning.

DR. MARX: Mr. President, I should like to take the liberty to point out that I announced the witnesses three days ago to the Prosecution.

THE PRESIDENT: Very well, counsel.

DR. MARX: With the permission of the Tribunal I shall now begin the case of the defense of the defendant Schroeder:

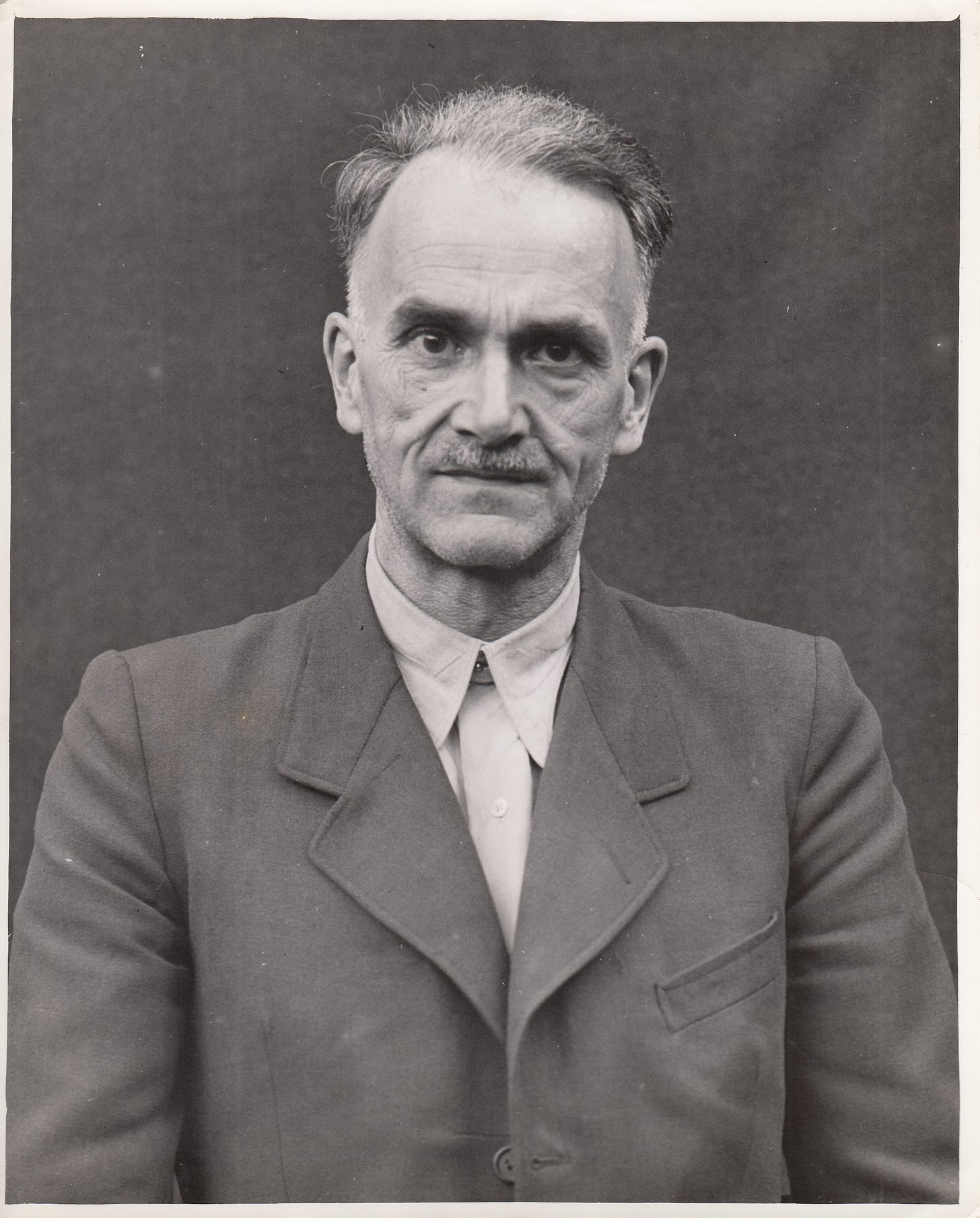

OSKAR SCHOREDER — DIRECT EXAMINATION

BY DR. MARX:

Q: Witness, please give the Tribunal some information about your youth your selection of a profession and your professional training.

A: I was born on the 6th of February, 1891, in Hannover. I grew up in my parents' home. I had a decided inclination toward natural science at an early age. At first I intended to become a teacher like my father but during my schooling I saw that was not the goal of my life and at the suggestion of relatives who were doctors I decided to study medicine. There was another inclination too. We were an old family of officials and soldiers There were many officers among my ancestors and so I decided to become a medical officer in order to combine these two inclinations, medicine and soldiery.

I went to the Kaiser Wilhelm Academy for Military Medical Training, the old training school for medical officers in the Prussian Army, and as it was connected with the Academy I studied medicine at the University of Berlin. At first I had to take basis military training and then in 1912 I took the preliminary examination and in 1916 I took the medical state examination. The beginning of the first world war in 1914 interrupted my studies so that in 1916 I was assigned to finish my studies and take the state examination. I was sent back to Berlin for this purpose. I participated in the war as a troop physician with various units. I was wounded and then I was in the field again and at the end I was Adjutant of a corps physician.

Q: Will you please give the details about your further service. After the first World War you remained in the Army. For what reason did you remain? What was your further career and your further training?

A: After the first World War the German Army was reduced to the well known one hundred thousand man Army. This meant that a large part of the officers had to leave the Army. Of the almost three thousand medical officer there remained only three hundred approximately. In general there was an urge to leave because the prospects in civilian practice, specialized practice as well as general practice, were favorable.

I myself tried to remain in the Army at the time because of the struggles going on in civilian practice, large economic struggles, health insurance and political societies, all these things were distasteful to me. I wanted to work as a doctor. I wanted to apply my knowledge and my influence in purely medical fields and so I tried to remain in the Army. And, I preferred to work for less money but to have work which was satisfying to me as a doctor instead of indulging in these economic struggles and other such things. My work was recognized. After I had worked as a surgeon for some time from '20 to '23 I had an extra duty in Koenigsberg, Prussia, in a Nose and Throat Clinic, Professor Rhese. And then from '23 to '25 I was assigned to the University Ear Clinic in Weurzburg, director Professor Manasse.

After this I had about seven years of clinical training and about two years of surgery and the rest of the time as Nose and Eye and Ear specialist. Then I became section physician of the Nose, Eye, and Ear section in the Post Hospital at Hanover and I was able to expend my knowledge in working with patients and also as troop physician with my unit.

Q: There you were transferred to the Army Medical Inspectorate. When was that?

A: From the first of January 31 I was transferred to the Army Medical Inspectorate. Through my long years of clinical work and my work in the Post Hospital in Hanover I had gained great experience in hospital work and care of patients and all things having to do with medical care of soldiers and I was sent to the Inspectorate and was the successor of Handloser to take over his duties. With the beginning of the reconstruction of the Wehrmacht the work for building up a large scale hospital system arose and I was in charge of dealing with new hospital buildings.

Q: Now, witness, from your work in the Army Medical Inspectorate how did you came to the Luftwaffe?

A: In 1935 the Luftwaffe was set up and at first it was seen that it was necessary to create its own medical service for the Luftwaffe. As a man in charge of this activity Oberstarzt Hippke was intended and an experiment man to be given him as an assistant. Since the five years, or more than five years, that I had spent in the Inspectorate had given me experience in this field and since I knew Hippke from my time as a student, my chief, Weldmann, considered me for this. And, in August 1935 I was transferred to the Luftwaffe and essentially I took over the same work which I had been doing in the Army Medical Inspectorate, that is, care of patients, hospitals, budgets, and now duties were added — testing flyers, medical equipment. This was my work.

Q: What was your preferred field of work?

A: My preferred field was construction of hospitals. The duties which were assigned me at this time had given me great insight into these things and my own clinical activity gave me special interest in these questions.

At this point I should like to say something about what I noticed from the examination of Professor Liebbrand here. In answer to a question — how was this question of professional ethics considered after 1933 and how was it decided — he answered:

One can answer this question by making a basic observation of the changes in the ethics of the medical profession. The doctor who hitherto for thousands of years, even before the Christian era, had the duty of helping the individual to the best of his knowledge and conscience This doctor, through the so-called national socialistic ideology, became a so-called biologistic State official.

That is, he no longer decided according to ethical principles of the pre-Christian and Christian Occident, in the interest of individual patients, that he was an agent of a class of leaders who did not care about the individual any longer, who considered the individual only an expression of the maintenance of a fictitious biologistic idea of race. And thus the heart was cut out of the medical profession.

If the doctor does not have any principal interest in the patient, who only carries out orders on behalf of a selective economy according to the laws of the Hippocratic oath he is not a doctor.

Against this formulation of medical ethics of the past period, thinking of the more than two thousand doctors who fell in the German Wehrmacht, I must object to this conception. These doctors fell while caring for the individuals entrusted to their care. They felt responsible for life and health of each of them.

Our work in the Inspectorate, as well as in the branch offices, was always clearly devoted to doing everything we could for the individual. The many hospitals which were built and equipped with loving care, the more than thirty hospitals which were built with my own assistance — they show perhaps more than words can how we endeavored to use medical science and to do everything we could for each individual person. That is certainly no corruption of the medical profession. That, in addition to this care for the individual, we considered the community. That is true of the military medicine of oil countries. That is nothing new.

And, in deliberate rejection of Professor Leibbrand's statement I must claim for us Wehrmacht physicians that we appropriated the eternal laws of the oath of Hippocrates and that we tried to fulfill them in accordance with the example of the great Master. Leibbrand apparently does not know his Hippocratic oath so well if he always emphasizes the individual patient. The great work of Hippocrates on air, water, and situation, which we might today call a text book of general Hygiene — this book speaks for the consideration of the community as well as the individual patient.

Q: Witness, what was your further career after the beginning of the War

THE PRESIDENT: Before proceeding the Tribunal will be in recess again for a few minutes.

(A Recess was taken.)