1947-03-31, #3: Doctors' Trial (afternoon)

(The hearing reconvened at 1330 hours 31 March 1947)

THE MARSHAL: Persons in the Court room will please find their seats.

The Tribunal is again in session.

THE PRESIDENT: The Tribunal has only just now received the statements by counsel for the defendant Sievers concerning the two witnesses which were referred to by counsel this morning. The Tribunal will examine this statement and announce its ruling as soon as possible.

The Tribunal now desires to announce that the Tribunal will recess at 3:30 o'clock Thursday afternoon of this week until 9:30 o'clock Tuesday morning following.

The Tribunal will be in recess from Thursday evening until Tuesday morning.

DR. FLEMING (For the defendant Mrugowsky): Mr President, I have no further questions to put to the defendant.

MR. HARDY: Your Honors, in as much as the witness Horn is outside now and the representative of the Czechoslovakian delegation informs me that the witness desires to return to Czechoslovakia tomorrow, it might be advisable to call the witness Horn now before the cross examination of Mrugowsky by defense counsel.

THE PRESIDENT: That was my intention. Defendant Mrugowsky is excused from the stand and will resume his place and the Marshal will summon the witness Horn on behalf of the defendant Hoven.

JUDGE SEBRING: You will hold up your right hand and be sworn. Repeat after me:

I swear by God, the Almighty and Omniscient, that I will speak the pure truth and will withhold and add nothing.

The witness repeats the oath as follows:

I swear by God, the Almighty and Omniscient, that I will speak the pure truth and will add nothing.

JUDGE SEBRING: Repeat this last part of the oath again:

That I will speak the pure truth and with withhold and add nothing.

WITNESS: I will speak the pure truth and will withhold and add nothing.

JUDGE SEBRING: You may be seated.

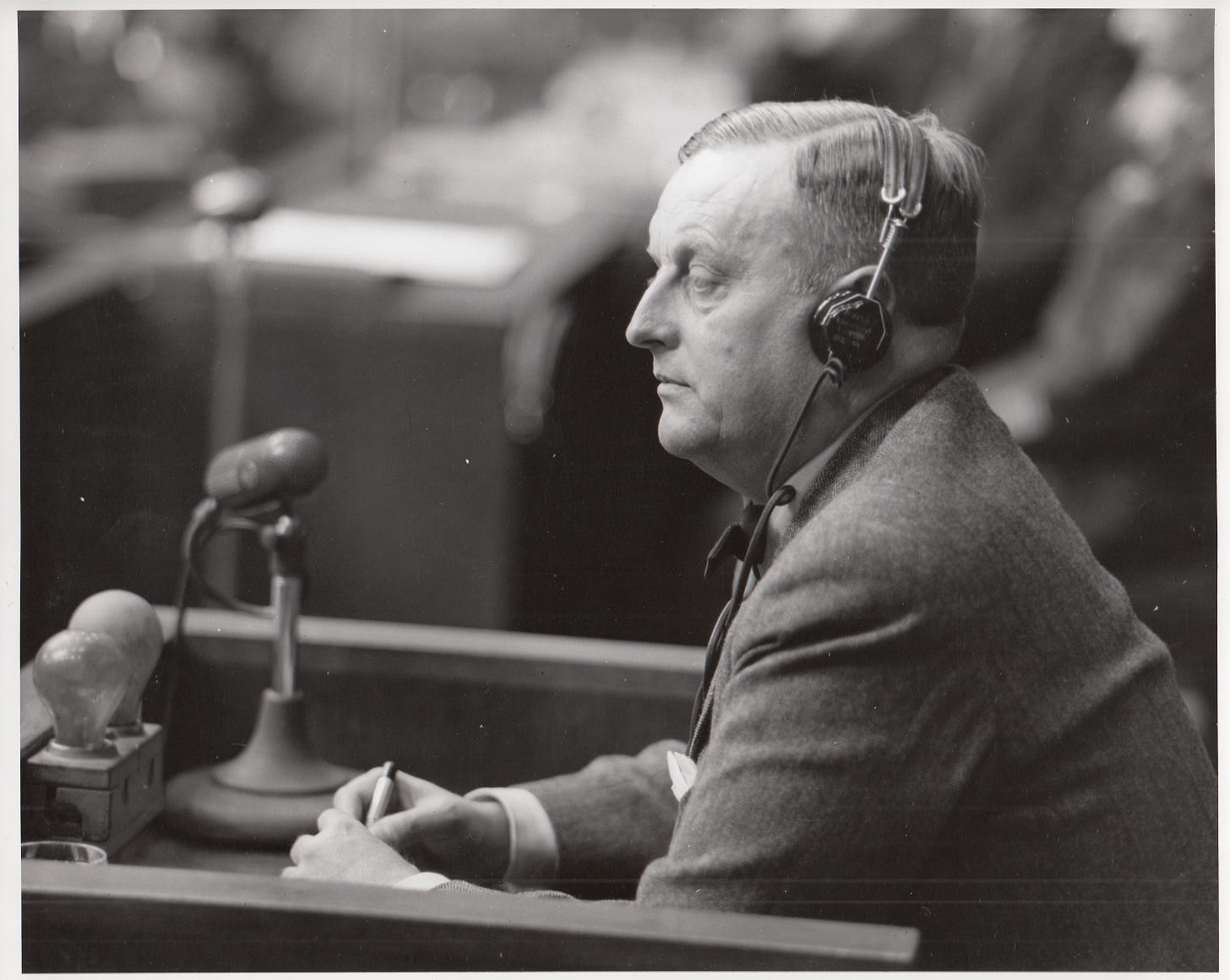

DIRECT EXAMINATION OF VIDESLAW HORN

BY DR. GAWLIK:

Q: Witness, will you please tell the Tribunal your name?

A: My name is Videslaw Horn.

Q: You are a doctor of medicine, is this true?

A: Yes, I am a doctor of medicine, a director of the hospital at Ihlava in Czecho Slovakia.

Q: When and where were you born?

A: I was born on the 2nd of November 1893 in Crbic.

Q: What is your nationality?

A: Czecho Slovakian.

Q: Please describe to the Court briefly your career?

A: My father was a doctor. I studied in Crbic and then in the medical faculty in Prague. I was a soldier in the first world war. I was assigned to a surgical unit under Hofrat Prof. Eisenberg in Vienna. After the end of the war I became an assistant of the surgical section in Brno. From there I went to my position in Hlava as director and surgeon. That was in 1924, 1925. I am married. My wife is from Pola, from Pola on the Adriatic.

Q: No, only your professional career. And what is your profession now?

A: As is I already said.

Q: When and for what reason were you arrested by the Germans?

A: I was arrested on the 17 July 1939 before the beginning of the war by the Gestapo. I was not interrogated. Later I was told that Germany was facing very serious events; that I would be put in protective custody for political reasons. My wife tried to find out what was wrong and the head of the Gestapo told her she should not expect me to come back. During 6 years I was never told why I was arrested. Nothing was explained to me.

Later we learned that this drive was called by the Gestapo the Benesh follower drive.

Q: What was your attitude toward national socialism?

A: As I wrote no articles and no books and hold no lectures, yet I was definitely opposed, and this can be seen from the documents which have been found now after the liberation in Czecho Slovakia. Kreisleitung Iglav asked the Gestapo to proceed against me with all possible moans.

Q: Where were you in custody?

A: I was in a Gestapo prison in Islawa, then in a collecting camp at Snolna, in the fortress prison Speilberg in Brno, and then I was sent to the famous Gestapo prison Polizeigefaenghis in Berlin where I did medical service, but suddenly I was locked up separately. I was locked up for six months without any reason being given. I had no ventilation. It was in the middle of the summer. Only later did I learn why this procedure had been taken with me. I took a trip through the prisons of Germany. I was in a prison in Vienna, Salzburg, Munich, Plaven and finally in Buchenwald.

Q: When did you come to the concentration camp Buchenwald?

A: On the 9th of December 1941.

Q: What was your activity in the concentration camp Buchenwald?

A: I was in the stone quarry but I was not there very long. Then I was in conversation with the Czech Liaison man. The Czech Liaison man said when Dr. Hoven came back from Leeds I would not stay in the stone quarry. I was also in the penal company and the liaison man, Dr. Seidak assured me I would not stay there. It was reported that Dr. Hoven would come back from Christmas leave on the 29th of December, and I was to be released on that day. Dr. Hoven immediately took me into the hospital. Dr. Hoven did not even examine me. I was accepted there as a patient.

Q: What was your position after the liberation of the camp by the Americans?

A: At the end of 1944 when the camp was enormously large, I believe we had in evidence more than one hundred thousand prisoners, I was the chief surgeon.

A: week after the liberation I was appointed. Chief of the Allied Medical Staff.

Q: You mentioned the name, Dr. Hoven, just now. Is this the same Dr. Hoven who is in the dock here?

A: Yes, he is in the second row, the fifth man from the right.

THE PRESIDENT: You will note for the record, that the witness has correctly identified the witness (defendant) Hoven.

BY DR. FAWLIK:

Q: What did you do in the hospital?

A: I came into the hospital as a patient. Dr. Hoven told me that there were no doctors there yet, you will be the first doctor, and the prisoners who work there do not understand their business. They all performed operations. They even performed appendectomies. They were afraid that they would lose their jobs. Dr. Hoven was right, as I realized later when I went to see a leading prisoner, Capo Weingartner, he said: "Comrade Horn, we do not need any doctors hero." I was a patient for three or four months, I believe. Dr. Hoven called me in for operations which I generally performed alone and went back as a patient to my bed. Suddenly I was released from the penal company and then I was put on the detail as a nurse. Generally I worked only in the operating room. I had the authority from Dr. Hoven to prepare for the necessary operations, and if necessary to carry out the operations. Generally, I was given an SS doctor such as Dr. Kraeft as assistant or Dr. Platzer and others. I performed the operations, and later when the SS doctors took an interest in the operations Dr. Hoven told me that the SS doctors would also perform operations. First, it was to be a theoretical discussion and then the operations were to begin. As an old surgeon at that time I pointed, out to Dr. Hoven that the operating technique required a certain amount of training, and Dr. Hoven said, "Do whatever you think is necessary and whatever you consider necessary." The young subaltern SS doctors did not like this and it was clear to me that they complained about me. They said my technique was very complicated. I said that they should begin with simple things like making knots, learning how to hold the instruments and so on.

Dr. Hoven was always on my side. He said a rule had to he made when a doctor can perform a breach operation, so I made a plan. The doctors first had to understand the matter theoretically and then they worked as assistants for about ten operations and then they performed twenty operations with my help and then we went on to other operations, such as appendectomies. We went into it gradually, and if it was not clear or if something went wrong, then we performed the operations on corpses. And later I was gradually let into the wards where the sick prisoners were and we had further training of the personnel, and later when other doctors came, that is prisoners, doctors, we had medical seminars. That was up to the time when Dr. Hoven was taken into custody.

Q: Please describe to the Tribunal the medical care in the Concentration Camp Buchenwald under Dr. Hoven?

A: When I came to the camp in December 1941 I believe that Dr. Hoven was not the chief camp physician. I believe his predecessor had typhus and he was merely representing him. The hospital had about three hundred beds, an internal and external section in three barracks. It had an x-ray station, a dental station, and a few auxiliary sections, like the laundry, etc.

Q: Did Dr. Hoven introduce improvements in the medical care?

A: We found in the camp that only nurses were treating the prisoners — no doctors. We could not understand this. When I was put to work there we discussed it once with Dr. Hoven and then further steps were taken. I should like to distinguish between improvements with regard to personnel and technical improvements. First, shortly after my appointment Dr. Hoven called in another doctor, Dr. Mathuschek who was used in the internal section. There was also a German doctor and I believe it was the assistant at the Dresden Orthopedic Clinic. He also worked there. Then later on other doctors came from Auschwitz to the camp and I gave a report that many doctors had arrived. I received an order from Dr. Hoven that I should bring those doctors to him. There were specialists — an eye specialist, Dr. Weick. He was used as an eye doctor in the hospital. There was Dr. Waniatta, a nose and ear specialists. He was used as a specialist at the hospital. And I point out that these are all Slavic doctors only Slavic doctors came from Auschwitz and, to go on, Dr. Pokerin, a Colonel, a nerve specialist. And, then later, I don't know whether Dr. Hoven was there yet or not, but there was a French X-Ray specialist, the professor of the French Medical Faculty in Dijor or Lyon, Professor Roussai.

That was all. And in Dr. Hoven's time a Tuberculosis Section was created. We did not have any specialist for that. I remember that there was a Jewish doctor in the camp, a tuberculosis specialist named Dr. Schnabel. It was impossible to use a Jewish doctor. Dr. Hoven got the idea that we can use him as a calfactor in the section. Dr. Schnabel was appointed but he dealt only with tuberculosis in the prisoners. Those were the improvements in the group of doctors. As for the training for the nurses. Dr. Hoven gave orders that they were to be trained and I was ordered to conduct this training. Then came the technical improvements in the camp. It grew slowly. We needed room. We asked for two hundred beds. Dr. Haven saw to it that two barracks were built with 200 beds. We had a pharmacy and the head of the pharmacy was an SS pharmacist. He was very reluctant to give out the drugs. Dr. Hoven saw to it that we get the drugs and if a report came from the pharmacy that the drugs were not available he got the drugs from Berlin. And now the matter of instruments occurs to me. In the operations on the abdomen, etc., we could perform but we did not have the instruments for trepanation for brain operations. Later, after the bombing — August 1944, it became very important and Dr. Hoven got these instruments with some difficulty in Berlin. I myself, although there were some surgical groups already working in the camp we had French surgeons, we bad Russian surgeons, we even had a Canadian at that time — and they all performed operations. I myself during 24 hours performed ever fifty brain operations which was only because I had received the instruments from Dr. Hoven. These were the technical things but there were other improvements, too, which had great value for us as prisoners. First, the matter of medicines. Then the medic ines were not available in the prison pharmacy Dr. Hoven permitted the medical non-commissioned officer, Wilhelm to go to Weimar or Jena and buy the medicines and we were very glad to pay for this.

When the prisoner specialists were not in the camp yet it happened that various eye cases came to me. I could not do anything also. They were well known people. For example, the well known painter, Joseph Taspek, who was a serious case. Taspek is a Czech. The name was well known in connection with President Masaryk. The man was afraid of losing his sight. I went to Dr. Hoven and Dr. Hoven sent a car to Jena regularly and sent the prisoners whom we could not help there. We doctors too were not specialists. An innovation in the camp was that a prisoner doctor was sent on an outside detail with a car to see what was going on. I myself was once sent on a detail about 80 kms. from Buchenwald where a prisoner, an anti-social, had broken his foot. He had been treated by a doctor there. I took him to the surgical section in the camp hospital Buchenwald.

Q: After this detailed description I shall submit to you NO-1063, Exhibit 328. This is the testimony of Schalker. On page 16 of the German, page 14 of the English translation, Schalker says:

The camp doctor Dr. Hoven played a very bad role and he is doubtless responsible for the death of numerous people because of completely inadequate medical care.

That is what the original Dutch text says.

A: I cannot remember who Schalker was and I do not want —

Q: Dr. Horn, I want to ask you the following questions. Did Dr. Hoven as camp doctor, play an extremely poor role?

A: No, of course not.

Q: Was Dr. Hoven responsible for the death of numerous people because of completely inadequate medical care?

A: That the health care in the camp, in spite of all the improvements, was for behind any civilian care, that is quite certain, but a description of how Dr. Hoven treated the prisoners in general would be more appropriate than what Schalker says about Dr. Hoven being responsible for inadequate medical care and that he ordered poor care — that is not true; or that he refused care to anyone, I cannot say that either. Dr. Hoven set up a network among the prisoners of liaison men. They were prisoners who could at any time speak to Dr. Hoven. They were all types — greens or blacks or whatever they were. As a concrete example, a liaison prisoner was x-ray laboratory assistant of the hospital, a "green" prisoner. The professional criminals were certainly a very peculiar group of prisoners. Generally we were political prisoners — I mean at the time of Dr. Hoven-that is at the end of December 1941 until the arrest in September 1943. During this time the majority of the political prisoners were hostages, that is, people who had not been interrogated by the Gestapo. For example, there was a large group of German prisoners there, mostly communists but there were some social democrats; there was a large group of Dutch hostages; then there were Czech hostages; and there were Poles. The Poles had a very special position. The political section of the camp, that is the Gestapo section, treated them quite differently than it treated the rest of them. Through the liaison prisoners, Dr. Hoven was in contact with all these groups That was a very important measure. The people came and reported "There is a person sick here, something must be done", and it was always arranged that the prisoners should be brought to the hospital and then the camp administration did not like this. An order was issued that no prisoner can go to the hospital unless he reports to a Report Leader, that is, an SS man working in the camp; and then in all blocks, whether they were German, Czech, Jewish or criminals, we had a so-called medical guard.

Dr. Hoven, in effect, told the SS "No prisoner may come into the hospital directly" and then he said "Only medical guards—" but they had a different name at the time of Dr. Hoven, "medical men", — "Only he can bring them". In spite of these measures I saw that the senior block inmate, out of fear for the SS, kept back many a prisoner. "You don't need to go to the hospital, you are all right." He didn't mean it badly, but just to avoid difficulties. And then it happened that the man didn't need it. If the care was still inadequate in spite of this system, that was due to conditions — the conditions at the camp as such, the food, and everything—and if Schalker says here that Dr. Haven is responsible for this, I must say no. As proof of this statement I must say if I or other liaison prisoners asked for anything I cannot remember that the were ever refused.

Q: Was Dr. Hoven in any material way different from the other SS doctors?

A: That is quite a broad question. It is unfortunate that I cannot show you a film which should be called "SS going through a camp street". We soldiers of the first world war, soldiers of the Vienna Monarch, we knew what it was to serve before the Kaiser, to stand at attention, but what happened when an SS man marched through the camp, I believe that surpasses any idea of any conviction of what a normal civilian can imagine. There were various stages in such a thing. The big victory of the German nation in Russia, when the Fuehrer said that the Red Army can be wiped out by police measures; then the landing in Africa; then the bombing of the American flyers and I must emphasize that it was an important moment for us later, the bombing of Nurnberg; the advance of the Red Army—that was reflected in the conduct of the SS. In 1941 when I came to the camp, when the SS went through the camp street the prisoners had to lie down, some were slapped and they were very badly treated. At that time already, at the time when the German nationals at its height, Dr. Hoven acted as follows:

going around the camp without a cap and with his hands in his pockets was normal. Sometimes he spoke to people, to the prisoners, and it was even seen that the prisoners stopped him and spoke to him. I give a concrete example; Dr. Hoven was once stopped on the street by a prisoner. He said he should be released because there was something wrong in his family. Dr. Hoven could do nothing but never-the-less he went to the hospital and told the liaison man "Investigate this matter". Evan if he did nothing and merely had the thing investigated, that was a big advantage to the prisoners that one could at least talk to the SS officer. And so the answer to your question comes up.

Q: Think of the other SS doctors— was there any difference between Hoven and the other doctors?

A: I went through a whole series of SS prisons.

Q: How about Schidlausky, for example?

A: Dr. Schidlausky came to the camp, I believe, in November 1943. Dr. Schidlausky had a very bad reputation. I was examining a female inmate of the camp when I heard that Dr. Schidlausky had come to the camp. I did not know this SS man. The woman said I should kill her because she did not want to live if Schidlausky was in the camp. After a few days I saw that something was wrong. This SS man who was preceded by such a bad reputation, did not want to sign death certificates for prisoners who had died in the hospital from normal diseases, let us say pneumonia, and a peculiar situation arose, that we prisoners first had to initial this death certificate. A few of the prisoner doctors were authorized to do that and only then did Dr. Schidlausky sign them. In spite of this change in Dr. Schidlausky there was still a big difference. If the food was not well prepared, Dr. Schidlausky was told about it. He took no interest but said "We cannot do anything, there is a war on, we cannot get anything." And so, to sum up, I should like to say if something was missing, medicine, for instance, under Dr. Hoven, we simply went to the SS Hospital and got the medicine.

Under Dr. Schidlausky it was the other way around. He wanted to take the last medicine from the prisoners to the SS Hospital. That would show the difference best.

Q: How were the medicines taken from the SS hospital to the prisoners' hospital?

A: Drugs and medicines you could put in your pocket sometimes. But plaster was needed, for instance, for casts, and that was not so easy to carry. That was not approved and the prisoner who carried it would be punished. There were pigs in the camp and we had to pick up the garbage. Sometimes we transferred these things carefully hidden under the garbage.

Q: Please describe to the Tribunal the general conduct of the Defendant Hoven toward the prisoners, insofar as you have not already done so.

A: I have already told you most of it—that the prisoners stopped Dr. Hoven and talked to him, that he had the medicine men, that he had these medical guards, and then there were other separate matters. The first Czech ambassador in Switzerland, Scrava, was a prisoner. He had a stomach tumor. Dr. Hoven learned of it and had him taken, I believe by car, to the prisoner hospital and he had me called through the public address system. He said I was to report everything that Dr. Scrava needed and we succeeded in helping Dr. Scrava to the extent that today he has taken up his position as chief editor in Prague. Such things were not exceptional. There were operations announced where the SS doctors were to come. I was to perform an abdominal operation. It was my custom and it was sensible of me to report to Dr. Hoven before every operation. I never performed an operation without the knowledge of Dr. Hoven.

Then there was an orthodox Russian, Dr. Galsky, I believe his name was Papa Andre. He had been severely mis treated by the Gestapo.

The Soviet Union at one time had concluded a peace with the Church, the Hierachy, which mostly had called emigrated people to go home to Russia. It is probably not technically possible but it was permitted then to return to Russia. When this orthodox priest, Dr. Galsky, fell into the hands of the Gestapo, he was to sign a statement of the orthodox church that he would not go to the Soviet Union. The consequences were the usual ones with the Gestapo. The prisoner came into the camp in a terrible condition. We prisoner-doctors had a certain position there. I was told quite openly by the head of the camp, that is first or second head of the camp, "You won't have this nan long." Nevertheless we succeeded in keeping Dr. Galsky alive for a long time. We were certain when he was in the hospital that Dr. Hoven would have no objections. Dr. Galsky later died because of the terrible food conditions in the camp.

Q: How about the hair cutting?

A: Dr. Hoven had a peculiarity. He did not like prisoners without hair but to be allowed to keep your hair, that was a very complicated matter that had to go through Berlin. But in 3 months we always had our hair. It happened to me that after a week my privilege as a protectorate prisoner was taken away from and I was me given a red triangle, as protective custody prisoner, and I had to give up my hair. It did not take long before Dr. Hoven brought me a note that was to be allowed to keep my hair. Dr. Hoven made a very difficult situation for me once. He had a professional criminal as an x-ray technician and the man had no hair at all. Dr. Hoven decided that he was to be able to wear at least what hair he had a little longer. I was supposed to sign an application that the man was to get hair.

I did not sign it. I did not quite understand how he was to do that. When I gave up this problem I saw that Dr. Hoven himself had written down that the man was suffering from a hair disease and he really got the approval. Jews also got permission from him, for instance, Jerlinek, the nurse from the tuberculosis ward, and others.

Q: What do you know about Hoven's killing of professional criminals?

A: I saw no such killings, either of these habitual criminals or of anyone. Certainly Hoven divided the prisoners as follows: There were decent prisoners and then there were prisoners who were not so decent. This was not the division that the SS officials made, this was a division depending on how the prisoners behaved; this was not the way Dr. Hoven classified them but the way the prisoners themselves classified the other prisoners. If I reported anything, a great deal depended on whether this prisoner I reported was a "decent" prisoner or whether he was not. The habitual criminals were part of this classification also.

DR. GAWLIK: I am just told that a change must be made in the microphone and that the meeting will be interrupted for a few minutes.

THE WITNESS: Among the habitual criminals, there were many moral offenders and they were very afraid of Dr. Hoven, But I did not see that he ever killed a habitual criminal.

Q: What point of view did you find in the camp about the justice that the camp inmates administered themselves?

A: Self administered camp justice was a very difficult problem. I myself, as a physician, was absolutely opposed to any harm that was done to human life or health. I was a physician and my fate there was somewhat better than that of most. My stiffest opponents in this matter were precisely the old political prisoners and I cannot condemn them; sometimes they got me into very difficult situations because of my attitude. With a mass of a few thousand person there, there must have then differences of opinion among them and there were crimes committed against the prisoners. We could not go to the SS, it was not possible.

Later when Dr. Schidlausky was in the camp, I was suddenly called away from an operation once and he told me that trouble was already beginning with the Czechs. I did not know what he was talking about, he told me I should give him an answer in two hours. I went into the camp and found out the following, a prisoner had been turned over to the camp who had accused sixteen people of our home town of Brne. I believe that ten of them were condemned to death. The relatives of these sixteen prisoners were already in the camp and they found out that this man had been brought in. They went after him, another group joined the chase and the consequence of all this was that the man died of a fractured skull. I was to initial the death certificate. I refused, however, because that death did not happen in the hospital.

Schidlausky said he would not sign it. It was the middle of summer, the dead man had already been lying around for two days and I did not know what to do.

Now, whether it was by accident or design, there appeared in the hospital a Roman Catholic Theologian, a young fellow and a member of one of the largest orders in Czechoslovakia. Dr. Schidlausky knew this man well and sometimes, half in jest and half in earnest, would ask; "What do you say about this as a priest?" His name was Peter Kajetan Deihl. He said "I repudiate any killings, I cannot approve of that, but I bring to your attention the fact that it is a great crime on the part of the SS to leave thousands of persons without any form of administration of justice or at least with only SS administration of justice." At this time the Red Army was a long way off and it did happen that the SS hung persons, including even a physician and the man was even asked before he was hang, what he had done.

Well, to begin we had a chance to turn the man over to the SS or not to do so. This was a very dangerous business. Those who had been decontaminated and had lice removed from them, could not be penalized and it was a very difficult matter to leave so many people without any form of justice. I said before that I repudiate all Killings and I cannot understand. This was a very striking thing to me and it was an internal problem always being discussed among us especially the illegal management of the camp and the under-ground management had its own attitude toward such killings.

For instance, in the case of a man who committed a homosexual act, he was simply killed.

Again I repudiate that, but if I go home and if a regular trial takes place on this matter, then I am convinced that for example the man, who had denounced the sixteen people to the Gestapo, ten of whom were hung, I would like to believe that before a regular Czech court he would be condemned to death.

Now, today, I would like to give my answer to that under-ground management. There is the man who perhaps is dead, out how many would have have denounced at that time had he not been killed; how many would, have died as a result of his acts if he had not been killed then.

Q: What do you know of the activities of Dr. Hoven in block 46?

A: I know this block; I spoke with Dr. Hoven and asked him what was to be done with block 46; it had been fenced off specially and I did not know at that time it was to be an experimental block where human beings were to be treated like guinea pigs. Dr. Hoven told me then that Dr. Mrugowsky wants to do something there and I did not discuss the matter further. I knew Dr. Ding at that time and that was enough for me; however, I was interested in this matter. The doctors slept in a room containing eight beds and among us there was a prisoner tailor. This man said to us, please don't give as typhus or anything of that sort. Whereupon we said of course not. He said, "I sew up clothes and the clothes are sent out to one place and another; there is no typhus there. I want to be perfectly sure I am in a perfectly clean room. In addition, Dr. Hoven comes to us so often, if he comes so often the clothes must be hygienic." Also there was a shoe repair shop. We could not go around in the operating room in wooden shoes and there were no soles in the camp.

I, was usual, simply turned to Dr. Hoven with the request for soles and received them from block 46, so I assume there was a shoe repair shop there also. Whether Dr. Hoven worked on the typhus experiments, I do not know as I was never in block 46.

Q: What do you know about Dr. Hoven's activities in block 50?

A: That was the vaccine production Institute of the Waffen SS. The origin of this institute with its proud name did not get to Buchenwald by accident. The SS doctors were changed, the situation among the prisoners was uncertain, there was a commando or detail on which the prisoners could be put away.

Long before the detail was founded, Dr. Hoven told us that it is possible that a hygienic institute would be set up in Buchenwald. This would perhaps do something among the lines of producing vaccines against typhus and he told us that he would have preliminary discussions concerning this in Berlin and again he mentioned the name Mrugowsky. After awhile Dr. Hoven came back and said that the institute would be set up. We were not serologists, we did not know anything about this business and it was a pretty important matter. We had heard that Dr. Ding would take it over and Dr. Ding was a man of varying moods. Then, we were finally sure that the institute would be there. We were interested because we know that the SS would not make the vaccines. Then, Dr. Hoven told us that no one knew that and, he knew of no one who could come from Mauthausen at the time. I was there in Mauthausen and there was a Czech serologist, a University Professor from Brno, by the name of Thomaschek.

I told this to Dr. Hoven, who jotted down the name, but Thomaschek did not come at first and came only later. After the liberation we found out that he had been taken from Mauthausen from Berlin and sent to Auschwitz.

In Auschwitz he was also under the charge of a serologist but the general situation in Auschwitz was much worse than it was in Buchenwald, so we merely did him harm by making this request for him. Well, the detail was set up and was called Block 50. Inmates were housed there, particularly Nacht und Nebel [night and fog] prisoners, Dutchmen, by the name of Biek, Robert, and many others. There were Jews. It was also a risk to send them there. Professor Fleck was one of them from the University of Lemberg, one of the best men in typhus research in eastern Europe; and Ding was chief.

Now, everyone was afraid of what would happen if Dr. Ding was in a bad mood, and everybody said that all of a sudden what would happen would be that the detail would be shifted to 46. Thus I can very well remember that these prisoners negotiated with Dr. Hoven or at least pointed out to him that either Block 50 should be subordinate to the Standort physician or Dr. Hoven would have to appoint somebody in charge of the personnel there. This took a lot of weight off everyone's mind in the camp, that is, that Dr. Hoven was Ding's deputy for Block 50.

Q: I come now to a different point. Were you the liaison man between the Czechoslovakian prisoners and Dr. Hoven?

A: Yes, I was one of the liaison men.

Q: Were you also a member of the underground camp management?

A: No, these differences of opinion regarding camp justice prevented that.

Q: What was your activity as liaison man for the Czech prisoners?

A: The following: We had been taken over into the Protectorate by Hitler. It didn't cost him anything to call a part of the prisoners honorary prisoners, and these honorary prisoners had certain privileges. One of these privileges was that now and then such a prisoner was freed. Now, Dr. Hoven always went immediately and said, "I can release about three people. Write me out three certificates." When we asked him which prisoners he wanted to have freed, he said, "Well, you talk it over in your Czech block and decide." In other words, this was done in a very democratic way.

We decided who was in greatest need of being set free. We talked this over and then I went back to Hoven and told Hoven that such and such a man would be a good man to set free. Such requests were what I took care of as liaison man.

Q: Did you frequently turn to Dr. Hoven with requests on the part of other inmates?

A: No, I have to correct you. There was something of an official system among the inmates. Everyone had access to Dr. Hoven regularly. Thus regularly we made requests. It was not a matter simply of requests but of suggestions, and all this was done very regularly.

Q: Did it ever happen that Dr. Hoven refused a proposal that you made in behalf of the prisoners?

A: We made several justifiable requests of Dr. Hoven, but these more serious questions, particularly medical matters, were all reported to Dr. Hoven and I cannot recall that any one of them was ever refused.

Q: At what time did the defendant Hoven help the prisoners?

A: I have already said that Dr. Hoven did already at the point when Germany was being most successful in the war, even then Hoven often helped the prisoners.

Q: In connection with this testimony I show you again Schalker's testimony from Document NO-1063, Exhibit Number 328, Page 14 of the English and 16 of the German translation. I quote verbatim what Schalker said:

Later, when it was almost certain that Germany would lose, he did many good things.

Now, in view of this testimony, I ask you again, did the defendant Hoven do good things for the inmates only after it became clear that Germany was going to lose the war?

A: I have already testified and I reiterate.

Q: What do you know about the prevention of "Nacht und Nebel" [Night and Fog] transports through Dr. Hoven?

A: We knew if something was done in the political department or if something concerned either us as individuals or as groups. First of all Dr. Hoven succeeded in relieving some prisoners from service in the political department.

From the Czechs, the present Landesminister [state minister] Dr. Dolansky, he brought us a number of things. But Dr. Hoven was a very precise informant, and so he came to us once with the news that there existed an N.N. commando. We didn't know what that meant, and we were told that it meant "Nacht und Nebel". We heard from Dr. Hoven that this was a horrible commando in Natzweiler, consisting mainly of Norwegians, and from the camp particularly Dutchmen were sent to the Nacht und Nebel commandos.

There were a few nurses among these Dutchmen, Masseur, Robert, then the well-known painter Piek, but there were also prisoners of whom the illegal camp management had said that they should stay in the camp. With this matter also recourse was taken to Dr. Hoven. Thus the camp management could not put prisoners at the disposal of Nacht und Nebel, and thus it was good not to get in touch with prisoners if they were a part of that commando. If they were in Block 50, they could be kept from being shipped to Natzweiler to the Nacht und Nebel commando.

Q: Do you know of other transports which Dr. Hoven prevented?

A: I can only tell you the broad outlines. Once a transport was standing outside the hospital with a few hundred persons, including all the old German political prisoners, Czechs of all professions, ministers, university professors, workers, members of parliament, and so on. I was quite sure that this commando could not go off if Dr. Hoven had not seen the commando. It was to be transferred somewhere to the north to Magdeburg, I believe, Magdeburg, Belsen. I sent someone out to Dr. Hoven's house with the request that he come to the camp. This was late afternoon. Dr. Hoven did come and immediately sent the transport back into the camp and said he wanted to examine the prisoners. Later we worked things out so that we could save the majority of the prisoners. We knew that this was an extermination commando because these were really weak persons and invalids.

Q: Can you tell the court the number of people who were saved by Hoven from this transport?

A: With the Germans, Czechs, a few hundred prisoners, it might have been two-hundred.

Q: Who had ordered this extermination, the commando?

A: That was certainly on the transport from the camp management, it was certainly a RSHA transport.

Q: Can you give the Court the names of a few persons whom Dr. Hoven saved from this transport to Madgeburg-Belsen?

A: All professions hero were represented, senators, ministers, representatives, all sorts of persons who were in this transport. Dr. Hoven did not concern himself with the names.

Q: Can you tell the Court about the release of members of United Nations, which Dr. Hoven brought about?

A: Of the United Nation, not too many of the United Nations came into question here. It was out of the question to send a Pole home, so any questions comes only of Dutchmen and with Czechs at this time. Later, French and others were included. Among the Dutch, whatever happened about that, that took place at the time after I was in the camp, and so far as Czechs are concerned, from time to time three, four or five were freed, as I have already described, but Germans also were set free, as one or two always being let out from time to time. I have described those events already.

Q: Please describe to the Tribunal how the defendant Hoven opposed the measures of RSHA?

A: The general rule was the beating of prisoners, and the SS gave them beatings; so all of a sudden a prisoner was told that he would receive twenty-five strokes, but this verdict had to be approved by the management, officially by the RSHA. Prisoners were so beaten that whole pieces of flesh were torn from their body; I have seen cases where the leg bone could be seen, or bone of the leg could be seen, and this affected all sorts of prisoners, whether they were habitual criminals, or any other kind.

Those were all taken to the hospital and treated. I can even remember a political prisoner from Bremen who simply could not stand to receive a beating of fifty strokes, so this beating was carried out under the supervision of a doctor. He was kept for months in a hospital, and I believe that the matter was sort of forgotten, because the camp commander who had brought this case up was relieved, and the man was then spared receiving the rest of his beating. Then he was reassured that in that connection he would not be beaten to death. Then there was the question of the Jews. The Jews were simply loaded into trucks, and disappeared, and a couple of days later people came and told us to take their names from the file index. These were transports in which there were never any medical examination to see if a person was fit to travel, whether they were seriously ill, or healthy. I believe this was the transport at the beginning of 1942 in which Jews were to be sent away on masse. They were all loaded on stretchers in the hospital, but as soon as they get around the corner, they took them off the stretchers, and disposed of them in another way. I myself intervened for a Jew named Cohen. He was sent from Czechoslovakia to Buchenwald, from the prison window I could see his wife with a newly born child in her arms, that from my window, and this sight of this woman so moved me, and I took what effort I could to help him. Cohen was carried around the corner like the others, I think that was the result of haying him freed. But this was in opposition to the RSHA, and then there were activities with the Nacht und Nebel prisoners. Then there was also individual actions. A young metal worker by the name of Stari, who is still alive today and in Freiburg, in a restaurant poked out Hitler's eyes in a picture, and he was brought to camp in a terrible condition. He was a good worker, and he was put to work in a quarry, but simply had sharpened the instruments in the quarry, and the leadership wanted him to stay there. One day after Hoven came and said, "Do you know Stari," I knew that story, and I said, "Yes, I did." Then Dr. Hoven said, "Things are not going too well with that man, we must take Stari into the hospital." a few days later he was called to the door, and either I or someone else was to examine him, and an answer came that he was sick, and then this was done, and in this way the man's life was saved.

This was also a measure taken against the RSHA. There was also an affair that concerned me. I was known in my region in Czechoslovakia, and this was the only case in which a representative of the Kreisleitung came to a camp to take a look at the situation. It was quite clear that he had come for that reason, to see to it that all possible measures were taken against me. At that time I was not present, and he really believed that these measures really were carried out, but these are not shown, and specific cases that occurred, and this to me, is one of Hoven's activities against the RSHA.

THE PRESIDENT: It will be necessary to suspend the examination of this witness at this time until tomorrow morning.

The Tribunal has considered the objection on the part of the Prosecution to the calling of the witnesses Topf and Borkenau on behalf of the defendant Sievers. These witnesses were applied for by the counsel for the defendant Sievers, sometime ago, and an order was entered by the Tribunal that the witnesses be called. This order was entered without any objection on the part of the Prosecution. The Prosecution, however, this morning moved that the witnesses be not called on the grounds that the statements made concerning their testimony were beyond the legitimate field of inquiry for the Tribunal. The Tribunal has examined the applications for the witnesses, and the memorandum filed today of Dr. Weisgerber, attorney for the defendant Sievers. The Tribunal is of the opinion that the testimony which counsel for the defendant Sievers proposes to elicit of these witnesses is within the field of competency before the Tribunal, and that the testimony may be appropriate to be heard before the Tribunal. The order is then signed by the Tribunal directing the witnesses be called. The order being dated February 4th, last, will be carried out.

The Tribunal will now recess until 9:30 o'clock tomorrow morning.

(The Tribunal adjourned until 1 April 1947 at 0930 hours)